MRSA isn’t just one bug. It’s two very different infections wearing the same name. One spreads in gyms, prisons, and homes. The other thrives in hospitals, nursing homes, and surgical wards. Both are resistant to common antibiotics like penicillin and methicillin. But beyond that, they’re almost opposites - in how they behave, who they infect, and how they’re treated.

What Exactly Is MRSA?

MRSA stands for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. It’s a type of staph bacteria that won’t die when you hit it with antibiotics like penicillin, amoxicillin, or methicillin. Staph bacteria live on skin and in noses of about 30% of healthy people without causing harm. But when they get into a cut, scrape, or surgical wound, they can turn deadly. And when they become resistant to key antibiotics, that’s when MRSA shows up.

For decades, MRSA was a hospital-only problem. It emerged after methicillin was introduced in 1959. Hospitals used antibiotics heavily, so the bacteria that survived were the tough ones - the ones with genetic armor. But in the late 1990s, something changed. Healthy people with no recent hospital visits started getting serious skin infections. These weren’t the old hospital strains. They were new, more aggressive versions - and they were spreading in the community.

Community MRSA: The Strain That Doesn’t Need a Hospital

Community-associated MRSA, or CA-MRSA, hits people who’ve never been in a hospital. Think athletes, kids in daycare, military recruits, prisoners, or people who inject drugs. It doesn’t care about your medical history. It spreads through skin-to-skin contact, shared towels, dirty gym equipment, or even just touching a surface with the bacteria on it.

CA-MRSA is genetically simpler. It carries a small piece of DNA called SCCmec type IV or V. That means it’s resistant to fewer antibiotics - but it makes up for it with weapons. Many CA-MRSA strains produce a toxin called Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL). This toxin kills white blood cells, turning minor skin boils into deep, painful abscesses. In rare cases, it causes necrotizing pneumonia - a fast, deadly lung infection that can kill otherwise healthy young adults.

USA300 is the most common CA-MRSA strain in the U.S. It’s responsible for about 70% of community cases. It’s also the strain you’ll find in injecting drug users, where poor hygiene, needle sharing, and skin punctures create perfect conditions for spread. Studies show injecting drug users are 14 times more likely to carry CA-MRSA than the general public.

What makes CA-MRSA scary isn’t just how fast it spreads - it’s how fast it kills. People with CA-MRSA skin infections often get better in a few days with just drainage and rest. But if it hits the lungs or bloodstream, things turn critical fast.

Hospital MRSA: The Multi-Drug Monster

Hospital-associated MRSA, or HA-MRSA, is the old-school version. It lives in places where antibiotics are used daily - ICUs, surgical units, dialysis centers. Patients here are often older, sicker, or have catheters, breathing tubes, or open wounds. HA-MRSA doesn’t need to be aggressive. It just needs to survive.

Its genetic armor is thicker. It carries larger SCCmec types (I, II, or III), which let it resist not just methicillin, but also erythromycin, clindamycin, and fluoroquinolones. In fact, 98% of HA-MRSA strains resist erythromycin. That’s a problem because those are often the go-to antibiotics when penicillin fails.

HA-MRSA doesn’t usually make toxins like PVL. Instead, it’s a slow, stubborn invader. It doesn’t burst into the body - it creeps in through IV lines, surgical incisions, or urinary catheters. Infections often turn into bloodstream infections, pneumonia, or surgical site infections. Recovery takes weeks. Hospital stays average over 20 days for HA-MRSA patients, compared to just 3 days for CA-MRSA.

And here’s the twist: HA-MRSA is losing ground. While it used to dominate hospitals, newer strains are showing up that look like CA-MRSA but carry HA-MRSA’s resistance genes. These hybrids are becoming more common - and they’re harder to treat.

The Blurring Line: When Community Strains Enter Hospitals

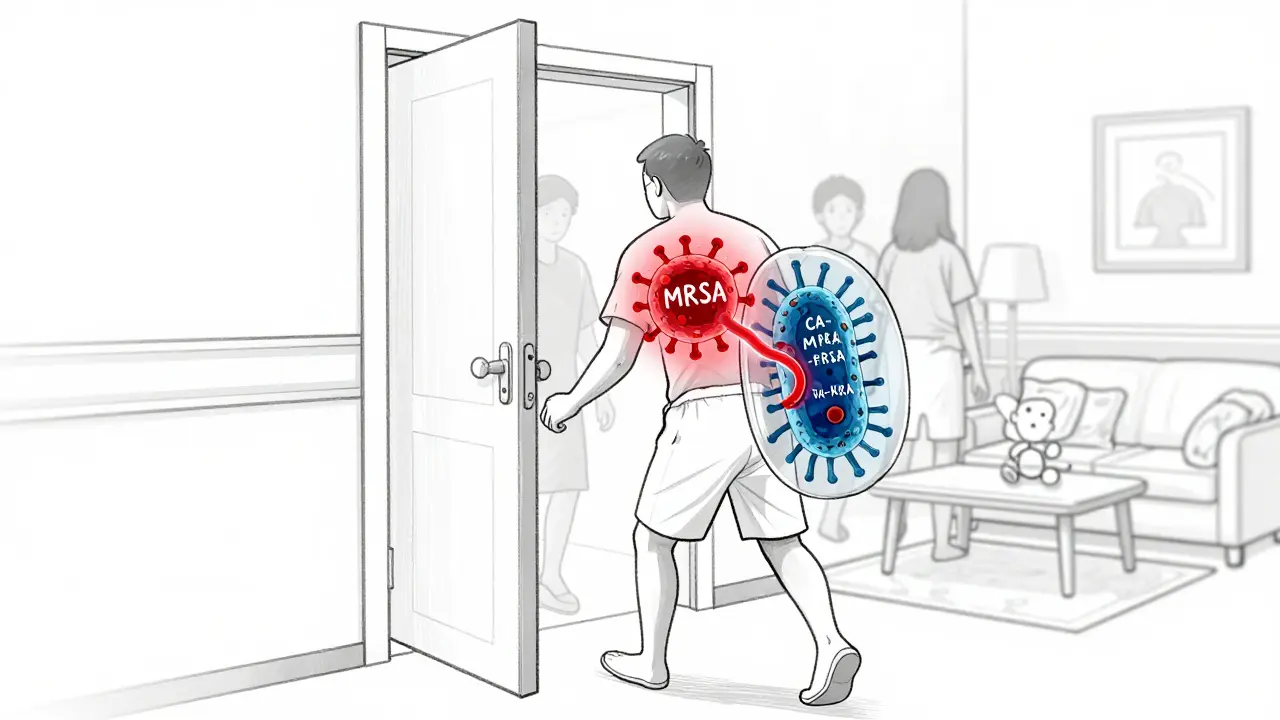

For years, doctors drew a clear line: CA-MRSA outside, HA-MRSA inside. But that line is gone. Today, about 28% of MRSA infections that show up in hospitals are actually caused by community strains. And 27% of infections that start in the community are caused by hospital strains.

How? Patients move between worlds. A person gets treated for a skin infection at home, then goes to the hospital for surgery. They carry CA-MRSA on their skin. A nurse touches them, then touches another patient. The hospital’s strict cleaning protocols don’t catch it because it’s not supposed to be there.

Even staff can be carriers. A nurse with a small, unnoticed boil at home might bring CA-MRSA into the hospital. A patient discharged with HA-MRSA might carry it back to a crowded apartment or homeless shelter, spreading it to people who’ve never seen a hospital.

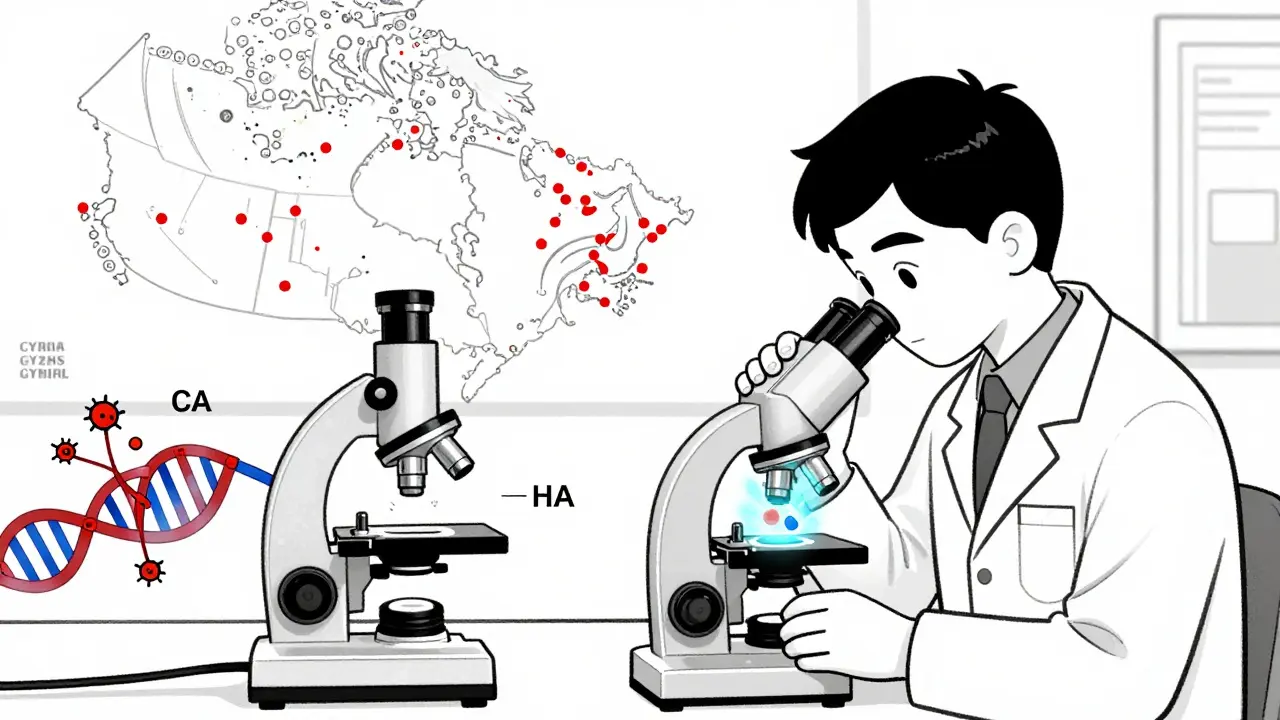

Canada’s data shows this clearly: over 20% of hospital MRSA cases are now caused by CA-MRSA strains. In some places, the community strain is becoming the main one in hospitals. That’s not just a shift - it’s a takeover.

How MRSA Is Treated - And Why It Depends on Where It Came From

Treatment isn’t one-size-fits-all. For CA-MRSA, the first step is often not antibiotics at all. If it’s a skin abscess, doctors cut it open and drain the pus. That’s it. About 70% of cases clear up without any pills. If antibiotics are needed, clindamycin works in 96% of CA-MRSA cases. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) works in 92%. Tetracyclines like doxycycline are also effective.

But HA-MRSA? Those are a different story. Because these strains resist so many drugs, doctors have to use stronger, last-resort antibiotics. Vancomycin is still the gold standard. Linezolid, daptomycin, or tedizolid may be used if vancomycin fails. These drugs are expensive, require IV infusions, and can damage kidneys or nerves.

The problem? If you assume a skin infection is CA-MRSA and give clindamycin - but it’s actually a hybrid strain with HA-MRSA resistance - the treatment fails. The infection spreads. The patient ends up in the ICU. That’s why hospitals now test MRSA strains in the lab before choosing antibiotics. No more guessing.

Prevention: Why Handwashing Isn’t Enough

Handwashing helps. But it’s not enough. CA-MRSA spreads in places where hygiene is hard to maintain: prisons, shelters, locker rooms, homes with multiple people sharing towels. You need more than soap.

For communities: Cover cuts. Don’t share razors, towels, or athletic gear. Shower after workouts. Wash clothes in hot water. If you have a boil, see a doctor - don’t pop it.

For hospitals: Isolation isn’t just for sick people anymore. Staff now screen patients for MRSA on admission, especially those coming from high-risk settings like nursing homes or prisons. If they test positive, they’re placed in isolation and treated with special cleaning protocols. Even visitors have to wear gowns and gloves.

But here’s the hard truth: you can’t control the community. And as CA-MRSA spreads, hospitals can’t keep up with screening every patient. The real solution? A system that treats MRSA as one problem - not two. Surveillance must track strains across hospitals, prisons, homeless shelters, and neighborhoods. We need to stop thinking of hospitals as islands.

The Future: Hybrid Strains and the End of Categories

MRSA isn’t staying in its lane. Strains are mixing. A CA-MRSA strain picks up a resistance gene from an HA-MRSA strain. Now you have a bug that’s both highly virulent and multi-drug resistant. These hybrids are already showing up in Europe and North America.

Doctors are no longer asking, “Is this CA or HA?” They’re asking, “What’s its genetic profile?” Labs now use DNA sequencing to identify strains, not just where the patient was treated. This is the future: precision treatment based on the bug’s genes, not its location.

And the CDC’s old definition of CA-MRSA - based on whether someone had a hospital visit in the past year - is already outdated. A person might have had a minor surgery five years ago. They’re not “at risk.” But they could still carry HA-MRSA. The system doesn’t match reality anymore.

What’s next? We need national tracking systems that monitor MRSA strains in real time - across all settings. We need better antibiotics. We need vaccines. And we need to stop treating hospitals as separate from the world outside their doors. MRSA doesn’t care about boundaries. Neither should we.

9 Comments

Alana Koerts

December 18 2025

MRSA is just another reason to stop trusting hospitals

pascal pantel

December 19 2025

HA-MRSA resistance profiles are a nightmare for antimicrobial stewardship programs-especially when SCCmec types I-III coexist with emerging PVL+ variants. We’re not just dealing with resistance anymore, we’re dealing with evolutionary convergence.

Chris Clark

December 21 2025

man i had a boil last year that looked like a small potato under my armpit-doc just lanced it, no antibiotics. 2 weeks later it was gone. people panic too much about staph. wash your hands, don't share towels, done. also why is everyone so scared of clindamycin? it's literally the cure for CA-MRSA

William Storrs

December 21 2025

you guys are making this sound like a doom scenario but honestly? we’ve got this. better hygiene, smarter screening, and a little common sense go a long way. if you’re lifting weights, shower after. if you’re in the hospital, ask if they’ve screened you. small steps, big impact. stay calm and carry on

James Stearns

December 23 2025

It is imperative that we reframe our public health paradigm to acknowledge the ontological collapse of the hospital-community binary in the context of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. The current nomenclature is not merely outdated-it is epistemologically incoherent.

Guillaume VanderEst

December 23 2025

in canada we’ve been seeing this shift for years-prisons and homeless shelters are the new epicenters. hospitals are just catching up. we need to stop treating this like a medical problem and start treating it like a social one. clean needles, clean showers, clean housing. it’s not rocket science.

Nina Stacey

December 25 2025

i think people forget that staph is everywhere like literally on our skin and in our noses and its not bad until it gets into a cut or something and then boom infection but like most of the time our body handles it and i think we overmedicate so much like why do we even give antibiotics for a small boil its just draining it and rest and i had one and i didnt take anything and it was fine

Dominic Suyo

December 26 2025

HA-MRSA is the ghost in the machine-silent, slow, and surgically precise. CA-MRSA? That’s the punk rock version: loud, violent, and full of toxins. But now? The punk just stole the ghost’s armor. Welcome to the new apocalypse. Vancomycin’s gonna need a bodyguard.

Sarah McQuillan

December 26 2025

you know what’s funny? the CDC still uses that 2005 definition of CA-MRSA-no hospital visit in the past year? that’s so 2008. my cousin got MRSA after a tattoo in 2023 and he’s never set foot in a hospital. but because he had a flu shot in 2022, some lab still labeled it HA. we’re diagnosing based on paperwork, not biology. it’s absurd.