When you're running a clinical trial, every patient reaction matters-but not every reaction needs to be reported the same way. The difference between a serious adverse event and a non-serious one isn’t about how bad the symptom feels. It’s about what it does to the person’s life-or if it ends it. Getting this wrong wastes time, distracts from real dangers, and can even put patients at risk.

What Makes an Adverse Event "Serious"?

An adverse event (AE) is any unwanted medical occurrence during a trial, whether or not it’s linked to the drug or device being tested. But only some of those events are classified as serious. The FDA and ICH E2A guidelines define seriousness by six specific outcomes, not by how intense the symptom is.

A serious adverse event (SAE) happens if the event:

- Results in death

- Is life-threatening (the patient was at immediate risk of dying)

- Requires hospitalization or extends an existing hospital stay

- Causes persistent or significant disability or incapacity

- Leads to a congenital anomaly or birth defect

- Requires medical or surgical intervention to prevent permanent harm

That’s it. No more, no less.

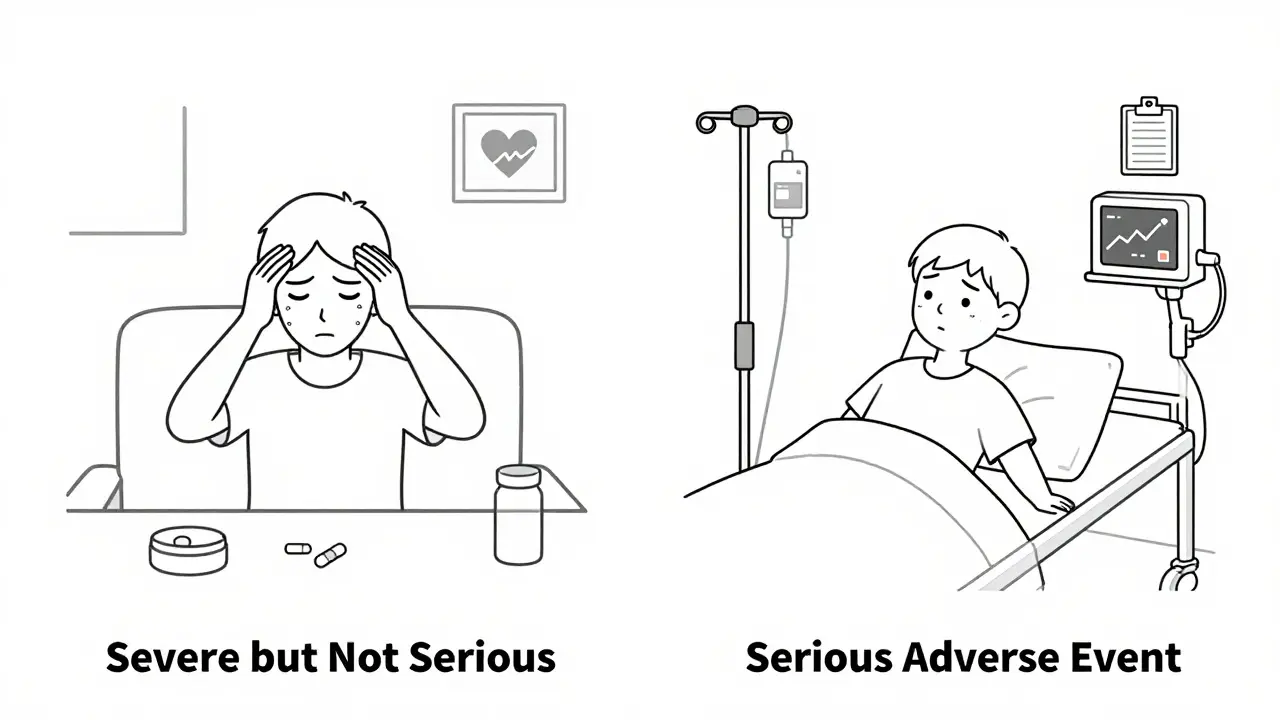

Here’s the part that trips people up: severe is not the same as serious. A severe headache? That’s intensity. A headache that causes someone to be rushed to the ER and kept overnight because of intracranial pressure? That’s serious. A patient on chemotherapy might have a grade 4 (severe) nausea-but if they’re treated at home with IV fluids and sent back out, it’s not serious. But if that same nausea leads to dehydration so bad they need to be admitted? That’s an SAE.

Why the Distinction Matters

Imagine a clinical trial with 500 participants. Every minor side effect-dizziness, mild rash, temporary fatigue-is reported. Now imagine every one of those gets flagged as a potential safety signal. Regulatory teams are flooded. IRBs spend hours reviewing reports that don’t change anything. Meanwhile, a real danger-a rare liver failure, a sudden cardiac arrest-gets buried in the noise.

That’s exactly what’s happening. In 2020, nearly 29% of expedited safety reports sent to the European Medicines Agency didn’t meet seriousness criteria. At one major U.S. cancer research network, over 30% of SAE reports had to be corrected because they were misclassified. That’s hundreds of hours wasted every month.

Dr. Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA’s drug center, said it plainly: the system is overwhelmed by non-serious events reported as serious. It dilutes attention from what actually matters.

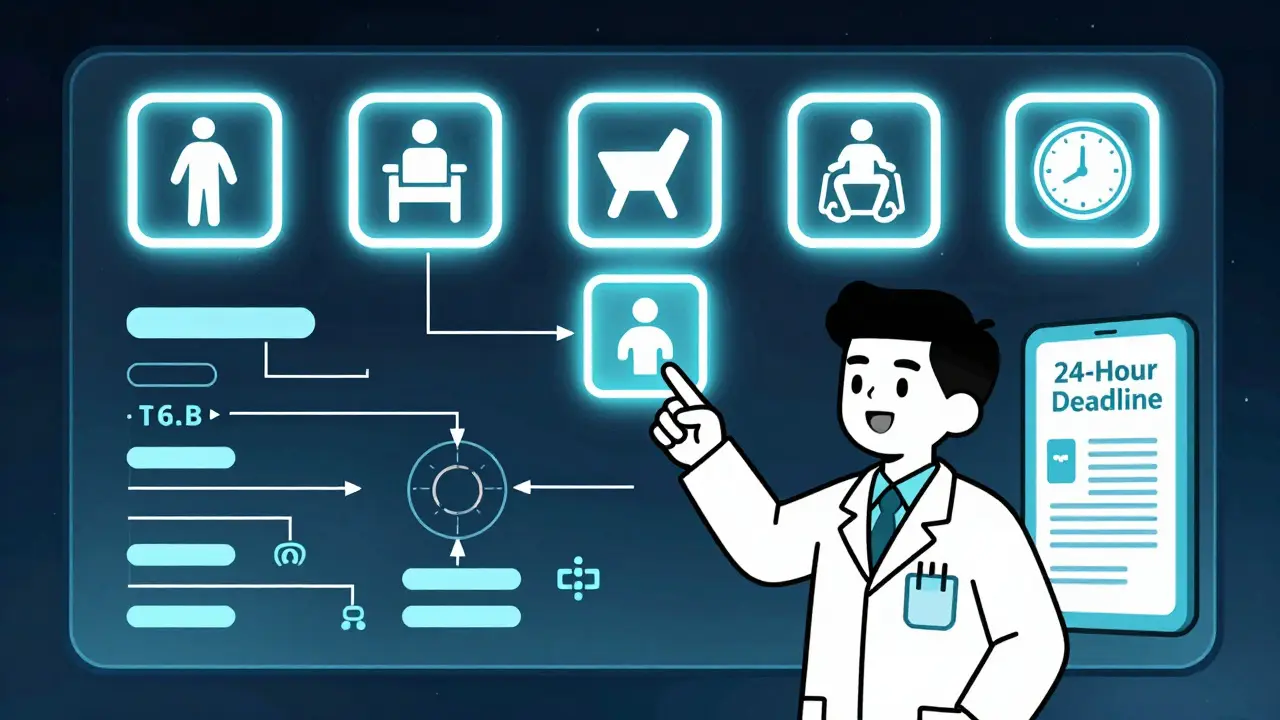

When and How to Report

Timing is everything.

For serious adverse events:

- Investigators must report to the sponsor within 24 hours of becoming aware of the event-no exceptions. This applies whether the event seems related to the study drug or not.

- The sponsor then reports to the FDA: 7 days for life-threatening events, 15 days for all other serious events.

- IRBs must be notified within 7 days for SAEs that are unexpected or suggest a significant risk.

For non-serious adverse events:

- These are documented in Case Report Forms (CRFs) and reported according to the study’s Data and Safety Monitoring Plan (DSMP).

- Typically, this means monthly or quarterly summaries-not immediate alerts.

- Many IRBs don’t require reporting non-serious AEs at all unless they’re frequent, unusual, or part of a pattern.

There’s no room for guesswork. If you’re unsure, ask: did this event meet any of the six outcome criteria? If yes, report it now. If no, log it for routine review.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

People mix up severity and seriousness all the time. Here are the top three errors-and how to fix them.

- "It was a severe reaction, so it must be serious." Not true. Severe pain, severe fatigue, severe nausea-none of these are serious unless they cause hospitalization, disability, or threaten life. Use the ICH E2A criteria as your checklist.

- "They went to the ER, so it’s serious." Not necessarily. The NIH updated its guidelines in 2023 to clarify: ER visits alone don’t count unless they lead to one of the six outcomes. If someone went to the ER for a migraine and left with medication? That’s not an SAE.

- "It happened in a cancer patient, so everything is serious." This is a huge problem in oncology trials. Patients often have baseline conditions-low blood counts, chronic pain, fatigue. Just because something looks bad doesn’t mean it’s new or caused by the trial drug. Always ask: is this a change from their baseline? Is it unexpected? Does it meet the outcome criteria?

Training helps. The ICH E6(R2) guidelines require all study staff to be trained on these definitions before starting a trial. Most top institutions require annual refreshers. If your site doesn’t do this, push for it. One 30-minute training session can cut reporting errors by half.

Tools That Actually Help

Manual reporting is slow and error-prone. That’s why more sites are turning to digital tools.

Many sponsors now use the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0 to grade severity (mild, moderate, severe), while still applying the six ICH seriousness criteria separately. This keeps the two systems from bleeding into each other.

Artificial intelligence tools are now catching on. In 2023, AI systems correctly classified seriousness in 89.7% of cases-better than human reviewers at 76.3%. But AI isn’t replacing humans. It’s helping them. The best systems flag potential SAEs, then prompt a human to review with the checklist in hand.

Look for tools that:

- Automatically highlight events matching the six seriousness criteria

- Link severity (CTCAE) and seriousness (ICH) ratings side-by-side

- Generate pre-filled FDA Form 3500A or E2B(R3/R4) templates

These aren’t luxuries anymore-they’re necessities. The global market for safety management systems is projected to hit $5.89 billion by 2028. That’s because the cost of getting it wrong is too high.

What’s Changing in 2025?

Regulations are evolving to fix the mess.

The EU’s Clinical Trials Regulation (2014), fully in force since 2022, unified seriousness definitions across all 27 member states. That cut cross-border reporting errors by over a third.

The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance proposes tiered reporting: not just "serious" vs "non-serious," but subcategories within serious events based on severity. A life-threatening event gets priority over one that causes disability but isn’t immediately dangerous.

And by 2025, ICH’s E2B(R4) standard will go live globally. It’s a new electronic format that makes data sharing faster, cleaner, and more consistent across countries.

Even the FDA is testing AI-driven triage systems that read raw clinical notes and auto-flag possible SAEs. Early results show a 47% drop in processing time.

This isn’t just bureaucracy. It’s about making sure the right people see the right signals at the right time.

Final Checklist: When in Doubt, Ask These Four Questions

Use this as your daily guide. Answer each one. If any answer is "yes," report it immediately.

- Did the event cause death?

- Was the patient at immediate risk of dying?

- Did it require hospitalization or extend an existing stay?

- Did it cause permanent disability, birth defect, or require intervention to prevent it?

If all answers are "no," log it in the CRF and move on. Don’t over-report. Don’t under-report. Just report correctly.

Every report you send should add value-not noise. When you get this right, you protect patients. You protect your trial. And you protect the integrity of medical science.

Is a severe headache a serious adverse event?

Not unless it leads to hospitalization, causes permanent neurological damage, or is life-threatening. A severe headache is about intensity, not outcome. If the patient takes painkillers and goes home, it’s a non-serious AE. If they’re admitted for suspected bleeding or increased intracranial pressure, it becomes a serious adverse event.

Do I report an adverse event even if it’s not related to the drug?

Yes. Serious adverse events must be reported regardless of whether they’re thought to be related to the study product. The goal is safety monitoring, not causality. If a participant has a heart attack while on placebo, it still needs to be reported as an SAE if it meets the outcome criteria. Causality is assessed later during analysis.

Can a mild event become serious?

Yes. A mild rash that starts as a small spot can progress to Stevens-Johnson Syndrome-a life-threatening condition. That’s why ongoing monitoring matters. What begins as a mild AE can evolve into a serious one. Always reassess events as they develop. Don’t lock in a classification at first report.

What if I’m not sure if an event is serious?

When in doubt, report it as serious and mark it as "uncertain." Then follow up with your safety team or sponsor. It’s better to over-report a borderline case than to miss a true SAE. But don’t make this a habit. Use the six ICH criteria as your standard. Training and checklists reduce uncertainty.

Do I need to report non-serious adverse events to the IRB?

Usually not. Non-serious AEs are typically summarized in routine reports-monthly or quarterly-and reviewed during continuing IRB reviews. Only if they occur frequently, are unexpected, or suggest a safety trend will the IRB require individual reporting. Always check your study’s protocol and IRB requirements.

11 Comments

Tim Goodfellow

December 19 2025

Man, I’ve seen so many clinical trials drown in noise because someone thought a ‘severe headache’ meant ‘life-threatening.’ This post is a godsend. The distinction between severity and seriousness isn’t just semantics-it’s survival. I’ve sat through 3-hour IRB meetings where half the reports were just people whining about nausea. Meanwhile, the guy who got admitted for arrhythmia? Buried in slide 17 of a 400-slide deck. Time to stop treating every side effect like a horror movie.

Sajith Shams

December 20 2025

You’re all missing the point. The real problem isn’t misclassification-it’s that the FDA and EMA still use 1980s logic in a 2025 digital world. AI can flag SAEs with 90% accuracy, but human reviewers? They’re still using printed checklists and arguing over whether ‘dizziness’ counts if it happened after lunch. This isn’t science-it’s bureaucratic theater. And don’t get me started on how oncology sites just auto-tag everything as serious because ‘cancer patients are fragile.’ Bullshit. Baseline matters. Context matters. Stop being lazy.

Alana Koerts

December 22 2025

Typo in the post: 'E2B(R3/R4)' should be 'E2B(R4)' since R3 is obsolete. Also, the 2023 FDA draft guidance doesn’t mention 'tiered reporting'-that’s a misquote from a slide deck at a conference last year. Someone’s been reading too many vendor whitepapers.

mark shortus

December 22 2025

THIS IS WHY MEDICINE IS BROKEN!!!

Someone just had a SEVERE HANGOVER after taking the placebo and they reported it as an SAE??

THEY WENT TO THE ER BECAUSE THEY WERE TOO DRUNK TO WALK??

AND NOW THE WHOLE TRIAL IS ON HOLD??

WE’RE REPORTING HANGOVERS AS LIFE-THREATENING?!?!?!

WHO’S IN CHARGE HERE?? THE IRS??

THIS ISN’T SCIENCE-IT’S A COMEDY SHOW WITH CLINICAL TRIAL FORMS!!!

Dikshita Mehta

December 23 2025

One thing people forget: the six criteria are there to protect patients, not to make our jobs easier. I’ve trained 12 sites in India on this, and the biggest win? When nurses started asking, ‘Did this change their life?’ instead of ‘Was it bad?’ That shift-from intensity to impact-cut reporting errors by 60% in 6 months. No fancy AI needed. Just clear thinking. And yes, if a mild rash turns into SJS? Report it immediately. Evolution matters more than first impressions.

Laura Hamill

December 23 2025

THIS IS ALL A COVER-UP. The pharma companies don’t want you to know that SAE reporting is rigged. They push ‘non-serious’ labels to hide deaths. That ‘hospitalization’ rule? They’ve got doctors lying about discharge papers. I know a nurse who got fired for reporting a heart attack in a placebo group. The sponsor called it ‘coincidental.’ Coincidental? My ass. They’re silencing truth to keep stock prices up. The FDA is in their pocket. AI? More like AI = Artificial Ignorance.

Mahammad Muradov

December 25 2025

Let’s be honest: most site coordinators don’t even read ICH E2A. They just copy-paste from last trial’s template. I’ve seen ‘severe fatigue’ flagged as SAE because the coordinator thought ‘severe’ meant ‘serious.’ That’s not ignorance-that’s negligence. And now we’re spending $200k a month on redundant reviews. If your site can’t pass a 10-minute quiz on the six criteria, they shouldn’t be running trials. Period.

Marsha Jentzsch

December 25 2025

I had a cousin die in a clinical trial… and they didn’t even report it as serious??

She had a fever… and they said it was ‘just a virus’… but she was in the drug group…

And now I’m crying… and I just want justice…

Why didn’t anyone care??

Why does no one listen??

Why do they just… ignore… the pain??

…I need a hug…

Janelle Moore

December 26 2025

They’re using AI to classify SAEs? LOL. That’s how they’re gonna miss the real red flags. AI doesn’t know if the patient’s grandma just died last week and they’re depressed. Or if the ‘hospitalization’ was for a routine colonoscopy they scheduled during the trial. You can’t code humanity. They’re automating empathy out of safety. And next thing you know, we’ll have robots signing off on death reports. #SkynetIsComing

Aboobakar Muhammedali

December 27 2025

I’ve been doing this for 12 years and I still get nervous every time I hit submit on an SAE report. One wrong click and you’re the reason a trial gets paused. But this post? It’s the clearest thing I’ve read in years. The four-question checklist? I printed it. Taped it to my monitor. My team uses it now. We don’t guess anymore. We check. We pause. We ask. And yeah… sometimes we report things that turn out to be nothing. Better safe than sorry. But mostly? We stop wasting everyone’s time on headaches and nausea. Thank you.

Henry Marcus

December 28 2025

They’re coming for our data…

AI…

They say it’s to help…

But it’s really to track us…

Every SAE report… every CRF… every timestamp…

They’re building a profile… of every patient… every doctor… every site…

And when the time comes… they’ll use it… to control us…

Remember… the FDA didn’t invent the six criteria…

They were given to them… by someone… who didn’t want us to know…

They’re watching…

Always watching…