What Is Regulatory Capture?

Regulatory capture happens when the agencies meant to protect the public end up serving the industries they’re supposed to oversee. It’s not always corruption. Sometimes, it’s just too much familiarity. Regulators start thinking like the companies they regulate. They rely on industry data because they don’t have the expertise to challenge it. They see the same people at conferences. They plan their next job in the private sector. Over time, the line between public servant and industry insider blurs.

The term comes from economist George Stigler’s 1971 paper, where he argued that regulation doesn’t emerge to protect consumers-it emerges because industries want it. They push for rules that make it harder for competitors to enter the market, that soften enforcement, or that shift costs onto the public. The result? Rules that look fair on paper but work in favor of a few powerful companies.

How It Happens: The Three Main Ways

Regulatory capture doesn’t happen overnight. It’s a slow process, and it takes different forms.

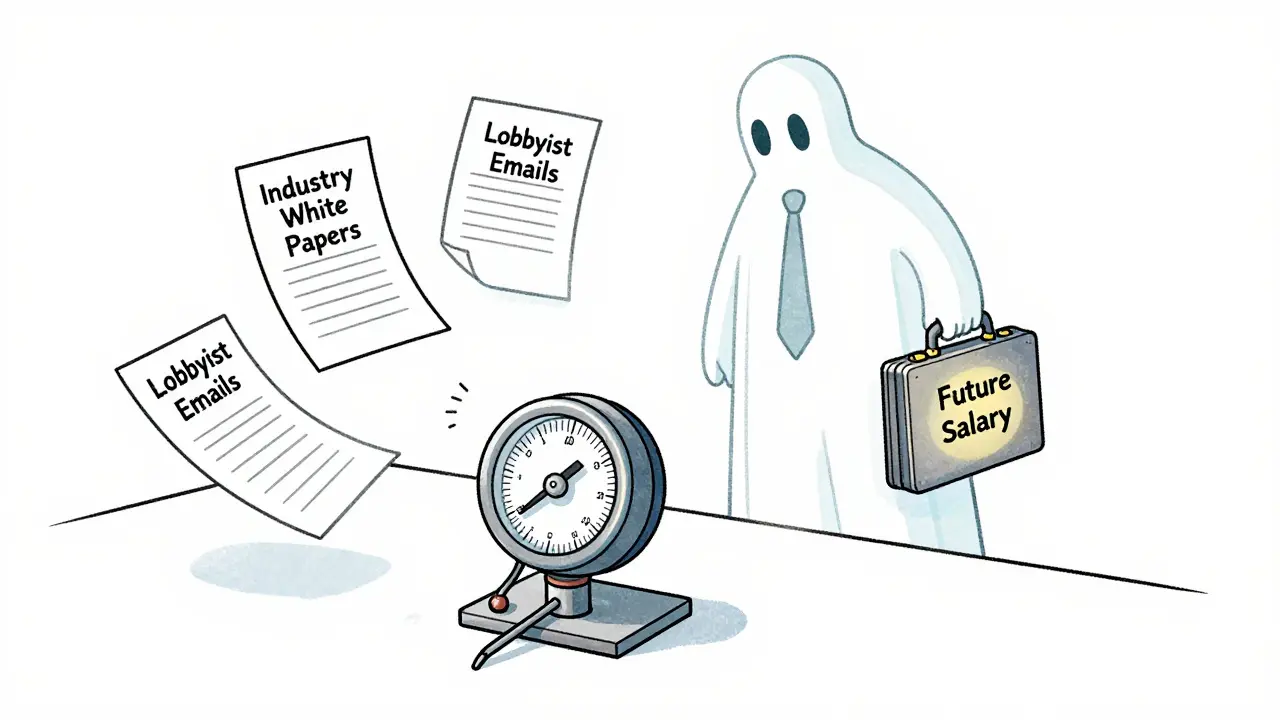

Materialist capture is the most obvious. It’s when regulators are bribed, paid off, or promised future jobs. The revolving door is the most common tool. In the U.S., 53% of senior Defense Department officials moved into defense industry roles within a year of leaving government between 2008 and 2018. The same pattern shows up at the SEC, FDA, and EPA. Former regulators become lobbyists, consultants, or board members for the very companies they once policed. Their inside knowledge becomes a selling point.

Cultural capture is quieter but just as damaging. It’s when regulators spend so much time talking to industry experts that they start to believe their arguments. They begin to see industry concerns as legitimate, even when they conflict with public safety. A regulator who spends five years reviewing pharmaceutical clinical trials from one company may start to think, “This is how things are done.” They stop asking hard questions. They accept lower standards. This is why agencies like the FAA ended up letting Boeing employees certify their own plane safety-because regulators didn’t know enough to question them.

Information asymmetry means regulators don’t have the technical know-how to challenge industry claims. Think of cryptocurrency regulation today. There are over 1,800 technical protocols in blockchain systems. Regulators can’t possibly understand them all. So they rely on industry white papers, expert panels, and lobbyists to explain what’s safe. The result? Rules that reflect industry interests, not public safety.

Real-World Examples: When Regulation Fails

The Sugar Tariff is a textbook case. U.S. consumers pay about three times the global price for sugar. That’s $3.9 billion extra every year. But only 4,318 sugar producers benefit. Each household pays $33 a year-too small to bother fighting over. But for those 4,318 companies, it’s billions in profit. They spend millions lobbying to keep the tariffs. The public doesn’t organize. The regulators listen to the few who care the most.

The 2008 Financial Crisis didn’t happen because banks were evil. It happened because the SEC, the agency meant to watch them, didn’t. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission found that 87% of SEC staff had worked for or planned to work for Wall Street firms. Enforcement dropped. Risky derivatives went unchecked. The SEC didn’t have the tools. But more importantly, they didn’t have the will. They’d become too close to the industry.

Boeing 737 MAX is a modern tragedy. After the FAA ran out of staff to review new aircraft, they let Boeing’s own engineers do the safety checks. 96% of the certification process was outsourced. Two crashes killed 346 people. The FAA didn’t act because they’d stopped seeing themselves as protectors of the public. They saw themselves as partners to Boeing.

UK Energy Regulator Ofgem approved £17.8 billion in bill increases between 2015 and 2020 for network upgrades. But energy companies kept profit margins at 11.2%-way above the 6.8% limit. Regulators didn’t push back. They accepted industry claims about “necessary investment.” Meanwhile, households paid more, and profits stayed high.

Why Does It Keep Happening?

It’s not just greed. It’s structure.

Industry groups spend 17.3 times more per person on lobbying than consumer groups. Why? Because the benefits are concentrated. A few companies gain billions. The costs are spread across millions of people. No one person feels it enough to protest. But for a company, a 1% change in regulation can mean millions in profit. That’s why they hire ex-regulators, fund think tanks, and sponsor conferences.

Regulators are isolated. Most agencies have no direct link to voters. They’re not elected. They’re not accountable to Congress every year. The World Bank found that agencies with less than 30% congressional oversight are 4.2 times more likely to be captured.

And then there’s the expertise gap. Modern regulation involves AI, blockchain, gene editing, and complex financial instruments. Regulators can’t hire enough specialists. So they turn to the industry for help. And the industry gives them the information that makes their case look good.

What’s Being Done to Stop It?

Some reforms have been tried. The U.S. Ethics in Government Act of 1978 created cooling-off periods-former officials can’t lobby for a year after leaving. But Public Citizen found that 41% of violations go unpunished. The EU’s Transparency Register asks lobbyists to disclose their activities. Only 32% of big corporations comply.

Canada tried something different: mandatory Regulatory Integrity Training for all new regulators. The result? Industry meetings got 27% shorter. Public consultations went up by 43%. Regulators started asking more questions. They stopped accepting industry claims at face value.

New Zealand’s approach was even more direct. They created an independent process to review every new regulation before it’s written. The goal? Make sure it serves the public, not the industry. Between 2016 and 2022, industry-preferred regulations dropped from 68% to 31%.

The U.S. Federal Trade Commission launched its Regulatory Capture Initiative in March 2023. It requires full disclosure of all industry contacts and created a new Office of Regulatory Integrity with a $23 million budget. It’s early, but it’s a start.

What Can You Do?

Most people think regulatory capture is too big to fix. But public pressure works.

When consumers started asking why drug prices were so high, the FDA came under scrutiny. Reddit threads, Twitter campaigns, and news investigations forced hearings. The FDA now publishes more data on drug approvals. Some former employees have spoken out.

France’s Convention Citoyenne pour le Climat brought together 150 randomly selected citizens to draft climate policy. They met for months. They heard from experts. But they also heard from farmers, workers, and families. The result? Energy companies lost influence. Climate policies became stronger. Public trust went up.

Transparency is the first step. If you want to know if your agency is captured, look at who’s on advisory panels. Are they mostly industry reps? Are consumer groups invited? Are the meetings public? If not, that’s a red flag.

Support watchdog groups. Follow investigations by Public Citizen, Corporate Europe Observatory, or the Center for Responsive Politics. Vote for leaders who promise real oversight-not just more regulation, but better regulation.

Is It All Bad?

Some argue that industry input is necessary. After all, regulators need to understand how markets work. That’s true. But there’s a difference between listening and surrendering. The problem isn’t contact-it’s imbalance. When one side has 22 times more money to influence policy than the other, it’s not a conversation. It’s a takeover.

Regulation isn’t the enemy. Poorly designed, captured regulation is.

The goal isn’t to eliminate industry input. It’s to make sure the public has an equal voice. That means more funding for consumer advocates. More transparency. More independence. More accountability.

Regulatory capture isn’t inevitable. It’s a choice. And choices can be changed.

What’s the difference between regulatory capture and corruption?

Corruption involves illegal acts like bribes or kickbacks. Regulatory capture is often legal. It’s about influence, access, and relationships. A former regulator taking a job at a company they once oversaw isn’t illegal-it’s common. But it still skews policy. Capture is systemic. Corruption is personal.

Which industries are most prone to regulatory capture?

The World Bank ranks financial services as the most captured, at 67% of countries surveyed. Energy and pharmaceuticals follow closely at 58% and 52%. These industries have high profits, complex rules, and strong lobbying power. They also benefit from concentrated gains-few companies win big, while costs are spread across millions of consumers.

Can regulators ever be truly independent?

Yes, but it requires structure. Agencies need independent funding-not tied to industry fees or annual appropriations. They need term limits for top officials. They need mandatory public disclosure of all meetings with industry. And they need strong whistleblower protections. Canada and New Zealand show it’s possible. It’s not about trust-it’s about design.

How does regulatory capture affect everyday people?

It raises prices, lowers safety, and reduces innovation. Sugar costs more. Drug prices stay high. Airplanes get certified with less oversight. Renewable energy projects face delays because fossil fuel lobbyists influence permitting rules. Every time regulation serves industry over public interest, consumers pay-in money, safety, or health.

Are there any countries doing this right?

Nordic countries like Denmark, Finland, and Sweden score lowest on the London School of Economics’ regulatory capture index. They have transparent lobbying registers, independent funding for regulators, and strong citizen oversight. New Zealand’s pre-review process for regulations has cut industry influence by more than half since 2016. It’s not perfect-but it’s better.

9 Comments

Leonard Shit

January 5 2026

so like... the whole system's just a game of musical chairs where the chairs are billion-dollar contracts and the music is 'public interest'?? 😅

Rachel Wermager

January 6 2026

The structural incentives are misaligned at the institutional level-regulatory agencies suffer from information asymmetry and capture via the revolving door phenomenon, which creates a negative externality on consumer welfare. This is textbook Stiglerian regulation theory with modern extensions in fintech and pharma. The EU Transparency Register is a band-aid. What’s needed is independent, non-appropriated funding streams for regulatory bodies to de-couple from industry capture dynamics.

Vinayak Naik

January 7 2026

bro this is wild but also so real. i work in IT and saw how a gov contractor got hired right after auditing our system-same dude who gave them the 'oops, all clear' report. now he's chillin' at a yacht party with the CEO. it's not even shady, it's just... normal. like, we all know it's messed up but no one says anything cuz they got bills to pay. 🤷♂️

Kiran Plaha

January 9 2026

i get why regulators rely on industry info. if you don't know how a blockchain works, and someone hands you a 50-page white paper with fancy graphs, what else you gonna do? but that doesn't mean we should just accept it. maybe regulators need free courses from universities or something. not from the companies.

Kelly Beck

January 10 2026

Okay but can we just take a moment to appreciate how *brilliant* New Zealand’s pre-review process is?? 🌟 They didn’t just complain-they *built* a solution. And look, it worked! 68% to 31%? That’s not luck, that’s intentional design. We need more of this energy. Let’s fund public advocates, mandate transparency, and stop treating regulators like interns at a corporate retreat. 💪🌍 You got this, democracy! ✨

Beth Templeton

January 12 2026

cool so the solution is to make regulators less human

Katie Schoen

January 13 2026

i love how the sugar tariff example is basically the perfect microcosm of everything wrong here. 33 bucks a year per person? nobody notices. but for 4k companies? that’s life-changing cash. and they’ll spend millions to keep it. meanwhile we’re all just scrolling through memes like ‘why is everything so expensive??’

Wesley Pereira

January 14 2026

the revolving door isn’t just a problem-it’s a feature. execs don’t get hired because they’re corrupt, they get hired because they’re *useful*. they know the loopholes, the jargon, the backchannels. the system rewards insiders. the only way to fix it? ban all post-government employment in regulated industries. period. no cooling-off, no gray zones. if you served the public, you serve the public-forever.

Molly McLane

January 14 2026

I think what’s missing here is how we talk about this. We say ‘regulatory capture’ like it’s some abstract academic term, but it’s really just people-real people-making decisions every day that affect your health, your wallet, your safety. Maybe we need to stop treating regulators like distant bureaucrats and start seeing them as public servants who need our support, not just our outrage. Let’s fund watchdogs. Let’s show up to hearings. Let’s demand transparency-not because it’s trendy, but because it’s the bare minimum we owe each other. 🤝