When you have diabetes, managing your blood sugar isn’t just about taking pills or injecting insulin. It’s about understanding what your numbers really mean - and how to use them every day to stay healthy. Two tools sit at the heart of this: your A1C test and your daily glucose readings. One tells you the big picture. The other shows you what’s happening right now. Together, they help you make smarter choices - but only if you know how to read them.

What A1C Really Tells You (And What It Doesn’t)

The A1C test measures how much glucose has stuck to your red blood cells over the past 2 to 3 months. It’s not a snapshot. It’s a summary. An A1C of 7% means your average blood sugar over that time was about 154 mg/dL. That’s the number most doctors aim for - but it’s not a one-size-fits-all target.

Here’s the catch: A1C can be misleading. If your blood sugar swings wildly - high one hour, low the next - your A1C might look fine, even if you’re in danger. People with brittle diabetes often have this problem. Their A1C is 6.8%, but they’re spending hours below 60 mg/dL or above 250 mg/dL. That’s not control. That’s instability. And A1C won’t tell you that.

Also, some health conditions mess with A1C accuracy. If you have anemia, kidney disease, or certain hemoglobin variants (more common in people of African, Mediterranean, or Southeast Asian descent), your A1C might read higher or lower than your real average. That’s why relying on it alone is risky.

Why A1C Targets Vary - And Who Decides Them

Not everyone should aim for the same A1C. The American Diabetes Association says most adults should target under 7%. But the American College of Physicians says 7% to 8% is better for many people with type 2 diabetes. Why the difference?

It comes down to risk. Tighter control - say, pushing A1C below 6.5% - can reduce eye, nerve, and kidney damage over time. But it also raises your chance of dangerous low blood sugar episodes. The ACCORD trial showed that people aiming for very low A1C had a 22% higher risk of death. That’s not a small trade-off.

In the UK, NICE guidelines are even more specific: 6.5% for someone newly diagnosed on one medication, 7% if they’re on multiple drugs. For older adults, especially those with other health problems or who live alone, 7.5% to 8% might be safer. A 75-year-old with food insecurity and heart disease doesn’t need a 6.5% A1C. They need to avoid fainting in the kitchen.

Personalization isn’t a luxury. It’s necessary. Your age, lifestyle, risk of hypoglycemia, and even your mental health matter. If chasing a low number makes you anxious, scared of food, or causes you to skip meals - that’s not health. That’s harm.

Daily Glucose Monitoring: Fingersticks vs. Continuous Sensors

While A1C gives you the long view, daily monitoring shows you the short-term. Two main tools do this: fingerstick meters and continuous glucose monitors (CGMs).

Fingerstick meters are cheap and familiar. You prick your finger, put a drop on a strip, and wait a few seconds. They’re accurate within ±15 mg/dL - but only if you use them right. A 2021 study found that 30% of home users get results off by 12% to 15% because they didn’t clean their hands, used expired strips, or didn’t code their meter properly.

CGMs - like the Dexcom G7 or Abbott FreeStyle Libre 3 - are changing the game. These tiny sensors sit under your skin and measure glucose in fluid between cells. They update every 5 minutes, 24/7. You can see trends: Is your sugar rising after lunch? Dropping overnight? Spiking after coffee? You don’t need to guess anymore.

CGMs also alert you before you go too low. That’s life-changing for people with hypoglycemia unawareness. A 2022 survey found 83% of CGM users felt more in control. But cost is a barrier. Even with Medicare coverage, out-of-pocket costs can hit $127 a month. For people on Medicaid, 32% report rationing strips because they can’t afford them.

The New Gold Standard: Time-in-Range

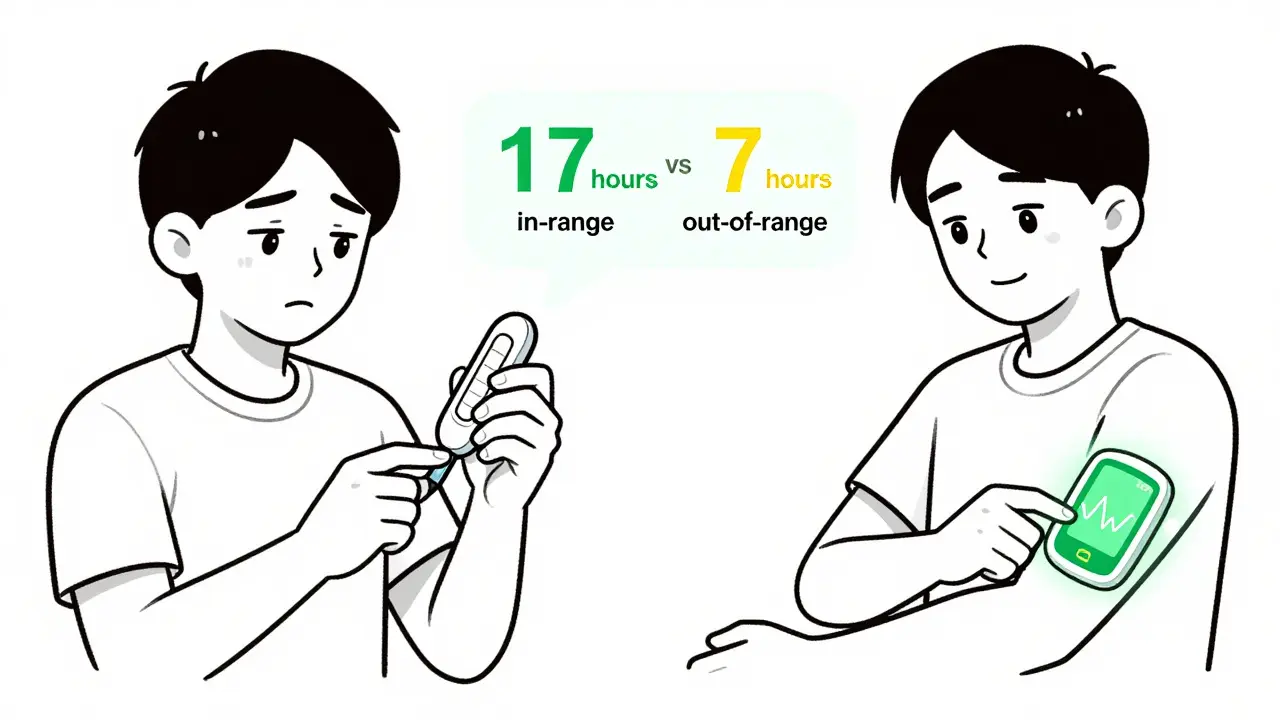

More doctors are moving beyond A1C alone. The new focus is on time-in-range: how many hours a day your glucose stays between 70 and 180 mg/dL.

The ADA now recommends aiming for at least 70% of the day in this range. That’s roughly 17 hours. You should spend less than 4% of the day below 70 mg/dL (that’s less than 1 hour) and under 1% below 54 mg/dL (less than 15 minutes).

Why does this matter? Because it’s more actionable. If your A1C is 7% but you’re only in range 50% of the time, you’re spending 12 hours a day too high and 4 hours too low. That’s not balanced. That’s dangerous. A CGM lets you see that pattern - and fix it.

For example: You notice your sugar spikes to 220 every morning after oatmeal. You switch to a protein-rich breakfast. Within a week, your morning readings drop to 130. That’s real progress. A1C wouldn’t have shown that.

How Often Should You Test?

If you use insulin, test your blood sugar 4 to 10 times a day. That’s not optional. Skipping tests means you’re flying blind. Medicare covers 100 test strips per month for insulin users - use them.

If you’re on pills or diet alone, you might only need 1 to 2 tests a day, maybe just before breakfast or after dinner. But even then, check more often when you’re sick, changing meds, or noticing new symptoms.

As for A1C: Test every 3 months if your treatment has changed or if you’re not hitting targets. If you’re stable and doing well, twice a year is enough. But don’t skip it. That lab result is your long-term report card.

Real Stories, Real Challenges

One user on Reddit, ‘Type1Since98’, said their doctor kept pushing for a 6.5% A1C - despite two emergency room visits from low blood sugar. They finally switched providers and got a target of 7.5%. No more ER trips. Better sleep. More confidence.

Another, ‘T2Mom65’, shared that after her first hypoglycemic episode at age 70, her doctor raised her target from 6.8% to 8%. She stopped fearing meals. She started cooking again. Her quality of life improved more than any number ever could.

These aren’t outliers. They’re common. A 2023 Diabetes Daily forum survey found 68% of users felt pressured by rigid A1C goals. Many said they hid their numbers from doctors because they were ashamed. That’s not health care. That’s fear.

What’s Next? The Future of Monitoring

Technology is moving fast. Hybrid closed-loop systems - like Tandem’s Control-IQ - now automatically adjust insulin based on real-time glucose. Real-world data shows they boost time-in-range by over 12% and lower A1C by half a percentage point.

Soon, we might see non-invasive options. Google and Dexcom are working on a contact lens that measures glucose through tears. It’s not ready yet - but it’s coming. By 2025, this could be a reality.

But tech alone won’t fix the problem. The biggest barrier isn’t the sensor. It’s access. In the U.S., 89% of people earning over 400% of the poverty line use CGMs. Only 12% of those below 100% do. That’s not a tech gap. It’s an equity gap.

What You Can Do Today

- Ask your doctor: What’s my personal A1C target - and why?

- If you’re on insulin, use CGM if you can. If you can’t, test more often - especially before meals and at bedtime.

- Track patterns, not just numbers. Write down what you ate, how you felt, and your glucose readings. Look for trends over a week.

- If you’re scared of low blood sugar, talk to your care team. There are tools, settings, and support systems that can help.

- Don’t let one bad A1C result define you. It’s a tool, not a judgment.

Managing blood sugar isn’t about perfection. It’s about progress. It’s about knowing your numbers - and using them to live better, not just survive.

What is a normal A1C level for someone without diabetes?

For someone without diabetes, a normal A1C level is below 5.7%. Levels between 5.7% and 6.4% indicate prediabetes, and 6.5% or higher is diagnosed as diabetes. These thresholds are set by the CDC and ADA based on decades of research linking A1C to long-term complications.

Can I trust my A1C if I have anemia?

No - not reliably. Anemia, especially iron-deficiency or chronic disease-related anemia, can cause A1C to read falsely high or low. If you have kidney disease, are pregnant, or have had a recent blood transfusion, your A1C may not reflect your true average glucose. In these cases, your doctor should rely more on daily glucose readings and time-in-range data from a CGM.

Why do some doctors want A1C below 7% while others say 7-8% is fine?

It depends on the patient. The American Diabetes Association recommends under 7% for most adults because studies show lower levels reduce complications over time. But the American College of Physicians says 7-8% is safer for many people with type 2 diabetes, especially older adults or those at high risk of low blood sugar. The goal isn’t a number - it’s balancing long-term health with daily safety and quality of life.

Is a CGM worth the cost?

For people on insulin, yes - even if it’s expensive. CGMs reduce hypoglycemia, improve time-in-range, and lower A1C over time. Many insurance plans, including Medicare, now cover them. If cost is an issue, ask about patient assistance programs. Some manufacturers offer free devices or discounted strips. The long-term savings from avoiding ER visits or hospitalizations often outweigh the monthly cost.

How often should I test my blood sugar daily?

If you use insulin, test 4-10 times a day - before meals, after meals, at bedtime, and if you feel low. If you’re on pills or diet alone, 1-2 times a day (like before breakfast or after dinner) may be enough. But test more when you’re sick, changing meds, or noticing unusual symptoms. Consistency matters more than frequency.

9 Comments

Greg Scott

February 19 2026

Man, this post really hit home. I’ve been type 2 for 12 years and my doc kept pushing me for 6.5% until I nearly passed out at the grocery store last year. Now I’m at 7.8% and I’m actually eating again. Who knew control meant not fainting?

Courtney Hain

February 21 2026

Let me tell you something the pharmaceutical companies don’t want you to know - A1C is a scam. It’s not even measuring blood sugar. It’s measuring how much glucose has stuck to hemoglobin, which is affected by red blood cell turnover, which is affected by inflammation, which is affected by… wait, do you even know what hemoglobin is? No? Then you’re being manipulated. The FDA knows this. The CDC knows this. But they keep selling the myth because insulin sales are up 300% since 2015. I’ve been tracking my glucose with a $12 watch from Amazon that blinks when I’m high. No strips. No sensors. Just vibes. And guess what? My A1C was 8.1 last year - but I’ve had zero complications. Coincidence? I think not.

Also, CGMs? Please. They’re tracking your data and selling it to Big Pharma. I saw a documentary. There’s a satellite. It’s beaming your glucose levels to a server in Switzerland. That’s why your numbers go weird when you’re on vacation. They’re testing new algorithms on you. I stopped using mine. Now I just eat kale and pray.

Ashley Paashuis

February 23 2026

Thank you for this thoughtful, evidence-based breakdown. I appreciate how you emphasized personalization over dogma - especially the point about quality of life being as important as numbers. As a clinical nurse specialist in endocrinology, I’ve seen too many patients internalize failure when their A1C doesn’t meet arbitrary benchmarks. The psychological toll of constant monitoring, coupled with societal pressure to achieve ‘perfect’ control, often leads to disordered eating, anxiety, and burnout. The goal should be sustainable health, not statistical perfection. Time-in-range is a far more meaningful metric, and its adoption in clinical practice is long overdue. I encourage providers to sit down with patients and co-create targets based on lifestyle, comorbidities, and mental well-being - not just guidelines.

Arshdeep Singh

February 23 2026

Bro, you think you’re smart because you read a study? Let me break it down for you like you’re 5. A1C is a lie. It’s made by white doctors in white labs who’ve never eaten biryani or pad thai. Your blood sugar spikes after rice? Of course it does. Your hemoglobin is different because you’re brown. They designed the test for white people. That’s why your A1C says 7.5 when you’re actually at 9.0. You need to test 10 times a day. Eat only meat. No carbs. No vegetables. No sugar. Just steak. And butter. And salt. Then your numbers will be perfect. Also, stop using CGMs. They’re made by Jews. Use a fingerstick. And pray to Shiva before each test.

Jeremy Williams

February 24 2026

As a first-generation immigrant from a community where diabetes is stigmatized as a personal failing, I’ve witnessed the silent suffering of elders who hide their meters, skip insulin doses, and eat rice anyway - out of cultural necessity, not negligence. The clinical guidelines you cite assume universal access, stable housing, and linguistic fluency - luxuries many do not have. I’ve seen grandmothers ration strips because their Medicaid copay increased. I’ve seen fathers skip meals to afford their child’s CGM. Technology is not the answer if the system refuses to make it accessible. We must demand policy change - not just better sensors. Health equity isn’t a buzzword. It’s a moral imperative.

Ellen Spiers

February 25 2026

It is imperative to note that the conflation of ‘time-in-range’ with ‘clinical efficacy’ is methodologically unsound without standardization of interstitial fluid dynamics, sensor lag correction, and calibration protocols. The ADA’s 70% threshold lacks robust longitudinal validation, and its reliance on CGM-derived metrics introduces selection bias, as these devices are disproportionately utilized by higher-income cohorts. Furthermore, the assertion that A1C is ‘misleading’ in the context of glycemic variability ignores the fact that standard deviation and coefficient of variation are already incorporated into validated algorithms such as the Glucose Management Indicator (GMI). To advocate for abandonment of A1C in favor of non-standardized, vendor-specific metrics is, frankly, premature and potentially hazardous to population-level outcomes.

Marie Crick

February 25 2026

You’re letting people die because you’re scared of a number. That’s not compassion. That’s cowardice.

Maddi Barnes

February 26 2026

Okay but have y’all noticed how the whole ‘A1C is outdated’ narrative is being pushed by CGM companies? 😏 I’m not saying it’s wrong - I LOVE my Libre, it’s life-changing - but also, why is every influencer suddenly talking about ‘time-in-range’ like it’s a new yoga trend? 🤔 And don’t even get me started on the ads for ‘glucose-friendly’ snacks that are just sugar with a fancy label. I once bought a $12 ‘diabetes-approved’ protein bar. It had 18g sugar. 18! I cried. But also? I’m glad I’m not alone. My mom said I was ‘too intense’ about my numbers. I said, ‘Mom, if I don’t track this, I’ll end up in a wheelchair before I’m 50.’ She shut up. 😘

Also, I switched from oatmeal to scrambled eggs + avocado. My morning spikes? Gone. I’m not a hero. I’m just hungry. And I’m not ashamed. 🥑💪

Benjamin Fox

February 27 2026

I'm an American and I say this: if you can't afford a CGM then you need to work harder. The system works if you work for it. No excuses. I use my Dexcom every day and I don't complain. If you're poor that's your fault. Also A1C is for losers. Only real people use sensors. 💪🇺🇸