Every year, thousands of patients in the U.S. and Canada face delays or disruptions in their treatment because a simple, low-cost generic drug isn’t available. It could be an antibiotic, a chemotherapy agent, or even an anesthetic used in routine surgery. These aren’t rare glitches-they’re systemic failures built into how generic drugs are made, sold, and distributed. And the root causes? They’re not about bad luck or natural disasters. They’re about manufacturing and supply chain decisions that have turned a vital part of modern medicine into a fragile, high-risk system.

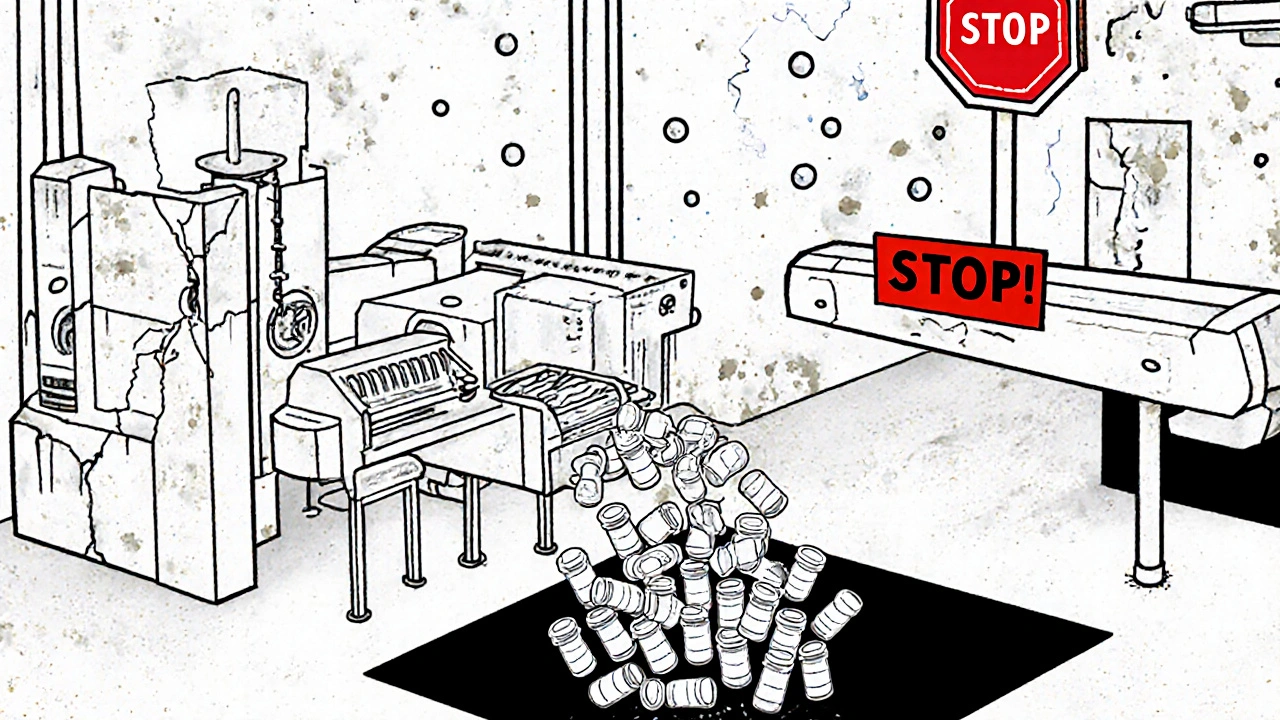

Manufacturing Problems Are the Main Cause

More than half of all generic drug shortages-62% according to FDA data from 2020-come down to one thing: manufacturing failures. These aren’t small mistakes. They’re major events that shut down entire production lines. A single case of contamination in a sterile injectable facility can halt output for months. Equipment breakdowns, poor quality control, or failure to meet FDA standards can trigger recalls or production halts. And because many generic drugs are made in just one or two facilities worldwide, when one goes offline, there’s no backup.

Take the case of sterile injectables like sodium bicarbonate or dobutamine. These are cheap, basic drugs used in emergency rooms and ICUs. But they require ultra-clean production environments. One mold spore or particle in the wrong place can contaminate thousands of vials. Fixing that means shutting down, cleaning everything from scratch, revalidating every machine, and waiting for regulators to approve the restart. That process can take six months or longer. Meanwhile, hospitals are scrambling to find alternatives-or ration what’s left.

Global Supply Chains Are Too Concentrated

Eighty percent of the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) used in generic drugs come from just two countries: China and India. That’s not a coincidence. These countries offer lower labor costs and less stringent regulatory oversight, making them attractive to manufacturers looking to cut costs. But it also means the entire U.S. supply chain depends on distant factories that are vulnerable to political shifts, natural disasters, or even local power outages.

In 2020, when COVID-19 lockdowns hit India, shipments of APIs slowed to a crawl. Hospitals ran out of antibiotics and heart medications. In 2021, a fire at a major API plant in China caused shortages of blood pressure and diabetes drugs for months. These aren’t anomalies. They’re predictable outcomes of a supply chain built on concentration, not resilience. And when a single facility supplies 90% of a drug’s API, there’s no safety net.

No Extra Capacity Means No Buffer

Unlike branded drugs, which are made with profit margins of 30-40%, generic drugs often sell for less than 15% profit. Manufacturers don’t invest in extra machines, backup lines, or surplus inventory because there’s no financial incentive. They run their factories at full tilt-just enough to meet demand, with zero slack. That’s called ‘lean manufacturing,’ and it works fine when everything runs smoothly. But when a machine breaks, a shipment gets delayed, or a regulator shuts down a line, there’s nothing to fall back on.

It’s like running a grocery store with exactly enough milk to meet daily sales-no extra cases in the back. One truck breaks down, and suddenly, no one can buy milk for a week. That’s the reality for generic drugs. And because these drugs are low-margin, companies don’t build redundancy. Why spend millions on a second production line for a drug that only makes $0.05 per pill?

Market Forces Push Manufacturers Out

The generic drug market isn’t just low-profit-it’s a race to the bottom. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), who control about 85% of prescription drug spending in the U.S., demand the lowest possible prices. To win contracts, manufacturers slash costs even further. Some cut corners on quality. Others stop making certain drugs entirely because they’re no longer profitable.

Since 2010, over 3,000 generic products have been discontinued. Many of them were once common, low-cost treatments. Now, they’re gone. And when a manufacturer exits a market, it doesn’t come back easily. Re-entering requires FDA approval, new equipment, and a guaranteed buyer-all of which are hard to secure when profit margins are razor-thin. The result? Fewer companies making more drugs, and each one becomes a single point of failure.

Lack of Transparency and Data

When a drug goes missing, patients and doctors often don’t know why. One in four U.S. drug shortage reports don’t even list a cause. Is it a manufacturing problem? A shipping delay? A regulatory hold? No one says. Hospitals and pharmacists waste hours calling distributors, checking bulletins, and guessing. That delays care and increases stress for everyone involved.

Unlike other industries, pharmaceutical supply chains aren’t transparent. Manufacturers aren’t required to report potential shortages until it’s too late. Even when they do, the information is scattered across different agencies and databases. There’s no real-time view of inventory levels, production schedules, or supplier health. Without that data, it’s impossible to predict or prevent shortages.

Canada Does It Better-Here’s How

Canada faces the same global supply chain risks as the U.S., but its shortage rates are lower. Why? Because it doesn’t rely on market forces alone. Canada has a national drug stockpile specifically for shortages-not just for disasters. It also has stronger coordination between regulators, hospitals, wholesalers, and manufacturers. When a shortage is predicted, they act together: reroute shipments, adjust dosing, or temporarily import from other countries.

In the U.S., the Strategic National Stockpile is only meant for bioterrorism or pandemics. It doesn’t hold antibiotics or chemotherapy drugs. There’s no federal system to monitor or respond to routine drug shortages. The result? Hospitals are left to manage crises on their own, often with outdated tools and no support.

What’s Being Done-and Why It’s Not Enough

There are proposals to fix this. The RAPID Reserve Act, introduced in 2023, aims to create a federal stockpile of critical generic drugs and offer tax incentives for domestic manufacturing. The FTC is investigating PBMs for anti-competitive behavior. The AMA is pushing to stop formularies from excluding drugs that are in adequate supply.

But these are band-aids. The core problem remains: the system is designed to minimize cost, not maximize reliability. As long as manufacturers are punished for charging more than a few cents per pill, and buyers demand the cheapest option regardless of risk, shortages will keep happening. No amount of regulation or stockpiling will fix a market that doesn’t reward safety, redundancy, or long-term planning.

The truth is, we’ve built a system that treats life-saving drugs like commodities-like toilet paper or pencils. But they’re not. They’re essential tools in medicine. And when the supply breaks, people suffer. Nurses delay surgeries. Cancer patients wait weeks for treatment. Diabetics risk complications because their insulin isn’t available. These aren’t abstract problems. They’re real, daily consequences of decisions made in boardrooms and regulatory offices far from the hospital bed.

Fixing this won’t be easy. It will require rethinking how we value generic drugs-not just as cheap alternatives, but as critical infrastructure. It will mean paying a little more to ensure there’s always enough. It will mean supporting domestic manufacturing, building backup supply lines, and holding middlemen accountable. Until then, the shortages will keep coming. And patients will keep paying the price.

10 Comments

kaushik dutta

November 28 2025

Let me tell you something straight from the factory floor in Gujarat-this isn't about regulation or profit margins, it's about systemic neglect by Western buyers who demand $0.02 per pill and then act shocked when the supply snaps. We make 70% of the world's APIs, but no one pays us to build redundancy. No one cares about buffer stock. You want reliability? Pay for it. Stop treating life-saving meds like discount toilet paper.

Katrina Sofiya

November 29 2025

Thank you for this deeply researched and sobering analysis. As a nurse who’s had to scramble for alternatives during shortages, I can confirm: patients don’t just ‘wait’-they suffer. We’ve substituted antibiotics with less effective ones, delayed chemo cycles, and watched families cry because insulin isn’t in stock. This isn’t a policy issue-it’s a moral failure. We must treat pharmaceutical infrastructure like power grids or water systems: essential, protected, and funded accordingly.

Sam txf

November 30 2025

Oh please. It’s all the damn PBMs and Big Pharma shills trying to keep prices low so they can gouge patients later with brand-name ripoffs. You think the FDA gives a shit? They’re understaffed and bribed by lobbyists. The real villain? The greedy middlemen who make billions off every script while hospitals beg for saline bags. Fix the middlemen, not the manufacturers.

doug schlenker

December 1 2025

I’ve worked in hospital pharmacy for 22 years. The worst part isn’t the shortages-it’s the silence. No one tells you why a drug is gone. No one tells you when it’s coming back. We get alerts from three different sources, all contradicting each other. It’s chaos. And the worst part? Nurses and doctors are expected to be miracle workers while we’re flying blind. We need a single, real-time national dashboard-not more reports.

Aarti Ray

December 2 2025

in india we make these drugs but no one pays us to keep extra machines running or hire more quality control staff. we get orders for pennies and told to deliver tomorrow. if you want reliability then pay for it. no one wants to pay more but everyone gets mad when the medicine is gone. its not magic its business

Hannah Magera

December 4 2025

My mom had to wait six weeks for her generic metformin last year. She’s diabetic. Six weeks. We called every pharmacy in three counties. No one knew why it was gone. No one could say when it’d be back. I didn’t know if she was going to be okay. This isn’t a supply chain issue-it’s a human crisis. We need to stop pretending this is just a cost problem.

Nicola Mari

December 5 2025

How is it possible that in 2024, a country with the GDP of the United States cannot guarantee basic medications? This is not incompetence-it is moral decay. The fact that we treat chemotherapy drugs like bulk commodities is an indictment of an entire system built on greed, apathy, and the devaluation of human life. Shame on every politician who voted against funding stockpiles. Shame on every PBM executive who profits from this.

Alexander Rolsen

December 6 2025

...so... let me get this straight... we outsource 80% of our life-saving drugs to two countries... who have... different regulatory standards... and then we’re surprised when things break? ...and you want to blame the manufacturers? ...the manufacturers are just following the rules... the rules set by YOU... the American consumer... who wants $0.05 pills... and then screams when the drugs disappear... you created this... you voted for this... you bought this... and now you’re mad? ...pathetic.

Olivia Gracelynn Starsmith

December 8 2025

Canada’s system isn’t perfect but it works because they treat drug access like public health not a marketplace. They have centralized procurement, mandatory reporting, and a national buffer. We have a patchwork of private contracts and reactive crisis management. The difference isn’t luck-it’s policy. We could fix this tomorrow if we chose to. But we don’t. Because we’d rather argue about who’s to blame than pay the price for safety.

Michael Segbawu

December 9 2025

AMERICA MADE THIS MESS BY OUTSOURCING EVERYTHING TO CHINA AND INDIA BECAUSE WE WERE TOO LAZY TO BUILD OUR OWN FACTORIES AND NOW WE WANT TO BLAME SOMEONE ELSE FOR THE COLLAPSE WE ASKED FOR. WE NEED TO BRING BACK PHARMACEUTICAL MANUFACTURING TO THE USA. NO MORE EXCUSES. NO MORE DEALS. NO MORE CHEAP DRUGS AT THE COST OF OUR LIVES. BUILD IT HERE. PAY FOR IT HERE. PROTECT OUR PEOPLE. OR GET OUT OF THE WAY