Why Immunosuppressants Are Lifesaving - and Risky

After a transplant, your body sees the new organ as an invader. That’s not a bug - it’s your immune system doing its job. But if left unchecked, it will destroy the transplant. Immunosuppressants stop that. They’re not optional. They’re the reason you’re alive today. But here’s the catch: these drugs don’t just silence your immune system’s attack on the organ. They silence it everywhere. That’s why infections, cancers, and organ damage become everyday risks.

Think of it like turning down the volume on a fire alarm. You stop the false alarms, but now you can’t hear the real fire. That’s why taking these meds exactly as prescribed isn’t just important - it’s survival.

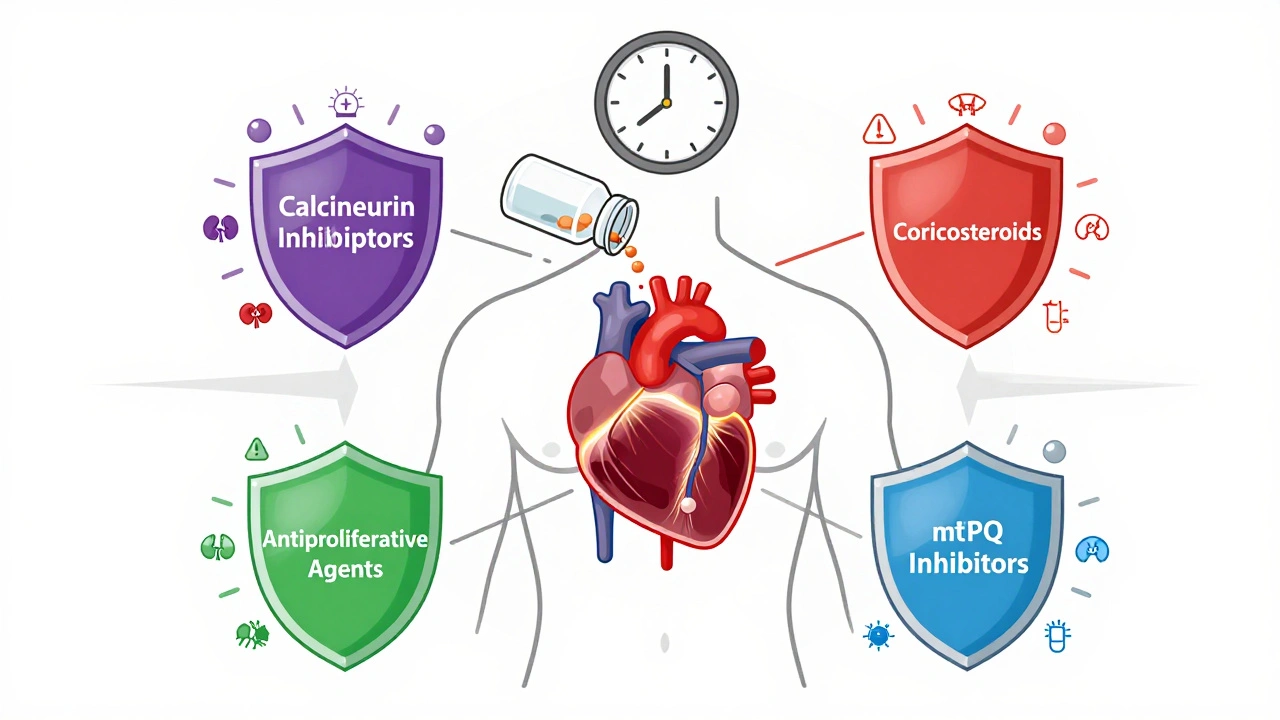

The Four Main Types of Immunosuppressants and What They Do

There’s no single magic pill. Transplant patients usually take a mix of drugs from four main classes, each with different strengths and dangers.

- Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine, tacrolimus): These are the backbone of most regimens. They block T-cells from attacking the transplant. But they’re hard on the kidneys. Up to half of patients develop long-term kidney damage from them. They also raise blood pressure, cause tremors, and increase the risk of skin cancer by 2 to 4 times.

- Corticosteroids (prednisone): These are powerful but messy. They reduce inflammation and rejection, but they also cause weight gain, diabetes in up to 40% of users, brittle bones (osteoporosis), and mood swings. Many doctors try to reduce or stop them after the first year.

- Antiproliferative agents (mycophenolate, azathioprine): These stop immune cells from multiplying. Mycophenolate is common, but it causes nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea in up to half of patients. It can also lower white blood cell counts, making infections more likely.

- mTOR inhibitors (sirolimus, everolimus): These are alternatives for patients who can’t tolerate calcineurin inhibitors. They’re easier on the kidneys but come with their own dangers: delayed wound healing, serious lung inflammation (pneumonitis), and high cholesterol. Everolimus has a black box warning for kidney clotting in the first 30 days after transplant.

Doctors pick combinations based on your organ, age, and other health problems. A kidney patient might get tacrolimus + mycophenolate + low-dose steroid. A heart transplant patient might skip steroids entirely and use everolimus instead.

Why Missing a Dose Can Cost You Your Transplant

One missed pill. That’s all it takes. A study of 161 kidney transplant patients found that 55% were nonadherent. Some skipped doses because they felt fine. Others forgot. Some couldn’t afford them. A few thought they could cut back since they’d been stable for years.

Here’s what happens when you skip:

- Within days: Your immune system wakes up. Inflammation starts around the new organ.

- Within weeks: Blood tests show rising rejection markers. You might feel tired, have swelling, or notice less urine output.

- Within months: The organ starts to fail. Scar tissue builds up. The damage is often permanent.

Heart transplant patients who miss doses are 3.5 times more likely to develop transplant coronary artery disease. Lung transplant patients who skip meds have a 2.8 times higher risk of late rejection. There’s no second chance. Once the organ is destroyed, you’re back on waiting lists - if you’re even eligible anymore.

How to Never Miss a Dose (Even When Life Gets Busy)

Adherence isn’t about willpower. It’s about systems.

- Use a pill organizer with alarms: A simple weekly box with morning and night slots works. Set your phone to remind you - twice. One at your usual time, one an hour later.

- Link it to a habit: Take your meds right after brushing your teeth, or with your morning coffee. Make it part of your routine, not a separate chore.

- Keep extra pills on hand: Always have a 3-day backup. Traveling? Pack twice what you need. Lost your meds? Call your pharmacy before you panic.

- Use apps: Apps like Medisafe or MyTherapy track doses, send alerts, and even notify your doctor if you miss a dose. Studies show these boost adherence by 15-25%.

- Ask for help: If you’re overwhelmed, talk to your transplant team. They can simplify your regimen. Maybe switch from three pills a day to two once-daily doses.

Cost is a real barrier. If you can’t afford your meds, don’t skip. Talk to your pharmacist. Many drug companies have patient assistance programs. Some states offer transplant medication subsidies. There’s help - you just have to ask.

What You Must Do to Avoid Infections

Your immune system is turned down - not off. That means even a cold can turn dangerous.

For the first 3-6 months after transplant, you’ll be on antibiotics and antivirals to prevent:

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV): A herpes virus that can cause pneumonia, diarrhea, and organ failure. If you get it, you’ll need months of antiviral treatment.

- Fungal infections: Like candida or aspergillus. These can spread from your lungs to your brain.

- Bacterial infections: Especially from cuts, dental work, or urinary catheters.

Everyday precautions:

- Wash hands for 20 seconds - before eating, after the bathroom, after touching public surfaces.

- Avoid crowded places during flu season.

- Wear a mask in hospitals or clinics.

- Don’t clean cat litter boxes or handle soil without gloves.

- Don’t eat raw fish, undercooked meat, or unpasteurized cheese.

- Get all recommended vaccines - but never live vaccines (like MMR or shingles shot) after transplant.

If you have a fever over 100.4°F (38°C), chills, or feel unusually weak - call your transplant team immediately. Don’t wait. Don’t take Tylenol and hope it passes.

Recognizing the Warning Signs of Rejection

Rejection doesn’t always hurt. That’s the scary part.

Here’s what to watch for by organ:

- Kidney: Less urine, swelling in legs or face, high blood pressure, fatigue, fever.

- Liver: Yellow skin or eyes (jaundice), dark urine, abdominal pain, nausea, itching.

- Heart: Shortness of breath, swelling in ankles, unusual fatigue, rapid heartbeat, dizziness.

- Lung: Dry cough, shortness of breath, fever, chest tightness, low oxygen levels.

These symptoms can be subtle. Many patients ignore them, thinking it’s just a cold or fatigue. But early detection saves organs. Regular blood tests and biopsies are your safety net. Don’t skip them.

What Happens If Your Transplant Fails?

If your organ stops working, stopping immunosuppressants becomes the right choice - but only under medical guidance.

Stopping suddenly can cause a dangerous immune surge. Your body may attack the dying organ violently, causing:

- Severe pain in the transplant area

- Worsening kidney or liver function

- Fluid buildup and breathing trouble

Your transplant team will guide you through a safe taper. You’ll also need support for dialysis, if you had a kidney transplant, or other life-sustaining treatments. The goal isn’t to rush off meds - it’s to do it safely, with dignity and care.

Long-Term Outlook: Living With the Trade-Offs

Transplant recipients live longer than those on dialysis or ventilators. But they still die younger than the general population. Why? The drugs.

After 10 years, about 1 in 3 transplant patients develops cancer. Skin cancer is the most common. Regular skin checks - every 6 months - are non-negotiable.

Heart disease, diabetes, and bone loss are also major killers. That’s why many patients now take statins, calcium supplements, and blood pressure meds alongside their immunosuppressants.

There’s hope. Newer protocols use lower doses of toxic drugs. Some patients, especially kidney recipients, are being weaned off calcineurin inhibitors entirely. Biomarker tests are starting to tell doctors exactly how much suppression each person needs - no more guesswork.

But for now, the rule is simple: take your meds. Every day. On time. No exceptions. Your new organ is counting on you.

Can I stop taking immunosuppressants if I feel fine?

No. Feeling fine doesn’t mean your immune system isn’t slowly attacking your transplant. Rejection can happen without symptoms. Stopping meds - even for a few days - can cause irreversible damage. Always talk to your transplant team before making any changes.

Do immunosuppressants cause weight gain?

Yes, especially corticosteroids like prednisone. They increase appetite, cause fluid retention, and change how your body stores fat. Many patients gain 10-20 pounds in the first year. Diet and exercise help, but you’ll need to work harder than before. Your care team can help you manage this without lowering your meds.

Are there natural alternatives to immunosuppressants?

No. There are no herbs, supplements, or diets proven to prevent organ rejection. Some, like St. John’s wort or grapefruit juice, can interfere with your meds and cause dangerous spikes or drops in drug levels. Always tell your doctor what you’re taking - even if it’s labeled "natural."

How often do I need blood tests?

Right after transplant, you may need blood tests twice a week. After 3-6 months, it usually drops to once a month. Long-term, you’ll likely need tests every 2-3 months. These check drug levels, kidney/liver function, and signs of infection or rejection. Skipping them puts your transplant at risk.

Can I have children after a transplant?

Yes - but it requires planning. Pregnancy is high-risk for transplant patients. Your meds may need adjusting. Some drugs, like mycophenolate, are dangerous in pregnancy and must be switched months before conception. Talk to your transplant team and an OB/GYN who specializes in high-risk pregnancies. With proper care, many transplant recipients have healthy babies.

What Comes Next? Monitoring, Adjustments, and Hope

Your transplant journey doesn’t end when you leave the hospital. It’s a lifelong dance between protection and risk. Your team will keep adjusting your meds - lowering doses, switching drugs, adding new ones - based on how you’re doing.

Today, we’re closer than ever to personalized immunosuppression. Blood tests can now measure your immune activity level. Some centers use these to reduce calcineurin inhibitors by 30-50% in low-risk patients - without increasing rejection. That means fewer kidney problems, less diabetes, and better long-term survival.

The goal isn’t just to keep you alive. It’s to help you live well. That means staying active, eating well, avoiding smoking, and keeping up with your screenings. It means never letting a missed dose become a missed chance.

You didn’t just get a new organ. You got a new life. Protect it - one pill at a time.

9 Comments

Evelyn Pastrana

December 9 2025

So let me get this straight - we’re told to take these drugs like they’re holy water, but the side effects could turn you into a walking diabetes-and-skin-cancer buffet? Thanks, medicine. 🙃 At least I can still cry about it.

Nikhil Pattni

December 9 2025

I’ve been reading up on this since my cousin got a liver transplant last year - and honestly, most people don’t realize that calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus have a narrow therapeutic index, meaning the difference between therapeutic and toxic is like 0.5 ng/mL. That’s why TDM (therapeutic drug monitoring) is non-negotiable. Also, did you know that grapefruit juice inhibits CYP3A4 and can spike tacrolimus levels by up to 300%? I’ve seen patients end up in ICU because they thought "natural" meant "safe." It’s not. Everolimus? Even worse - it’s a mTOR inhibitor, so it messes with mTORC1 and mTORC2 pathways, which is why you get hyperlipidemia and pneumonitis. And don’t even get me started on mycophenolate’s GI toxicity - it’s like your gut throws a tantrum every morning. You need to take it with food, but not high-fat food, because that alters absorption. So yeah - it’s not just about remembering the pill. It’s a full-time job.

Elliot Barrett

December 10 2025

Yeah, right. 'Take your meds or die.' Newsflash: I’m tired of being a medical guinea pig. Half these drugs are just glorified poison with a fancy label. And don’t give me that 'it’s your life' nonsense - I didn’t ask for this.

Sabrina Thurn

December 10 2025

The real kicker is that we’re still operating on 1980s-era immunosuppression protocols while the science has moved toward precision immunology. Biomarker-driven dosing - like the AlloMap or KidneyIntelX tests - can now quantify alloreactive T-cell activity and predict rejection risk without biopsy. We’re talking about moving from blanket suppression to targeted modulation. But until payers cover these tests, most centers stick to the old 'one-size-fits-all' combo of tacrolimus + MMF + steroid. It’s archaic. And the fact that we don’t routinely screen for CMV serostatus pre-transplant? That’s criminal. CMV-negative recipients getting organs from CMV-positive donors? That’s a ticking time bomb without prophylaxis. We know how to prevent this. We just don’t.

Lauren Dare

December 11 2025

Oh, so now I’m supposed to believe that skipping a pill 'can cost you your transplant'? Funny - because last time I checked, my insurance didn’t cover the $12,000/month for tacrolimus. So yeah, I’ll skip. And if I die? Well, at least I died on my terms.

Gilbert Lacasandile

December 13 2025

I really appreciate how thorough this is. I’ve been on tacrolimus for 7 years now and I still get nervous every time my levels dip. The pill organizer with alarms? Lifesaver. I even set two - one for 7 AM and one for 8 AM. My wife says I’m obsessive. I say I’m alive.

Lola Bchoudi

December 13 2025

For anyone struggling with adherence: don’t feel guilty. This isn’t about willpower. It’s about system design. Use Medisafe. Link it to brushing your teeth. Keep extras in your car. And if cost is the issue - DM your transplant center. They have financial navigators for a reason. You’re not alone. We’ve all been there. One pill at a time - that’s the mantra.

Morgan Tait

December 14 2025

I’ve been researching this for years. The government doesn’t want you to know this, but immunosuppressants are actually a Trojan horse for Big Pharma. They’re designed to keep you dependent - that’s why they never fix the root cause. And the skin cancer stats? Totally exaggerated. It’s the UV exposure from all those hospital visits, not the drugs. Also, have you heard about the 'transplant suppression conspiracy'? They don’t want you healing naturally because then they lose the monthly cash flow. I know someone who cured his rejection with turmeric and meditation. They kicked him out of the program. Coincidence? I think not.

Darcie Streeter-Oxland

December 16 2025

The assertion that nonadherence is associated with a 3.5-fold increase in transplant coronary artery disease among heart recipients is, in my view, statistically compelling. However, the absence of a citation to the original cohort study (presumably the 2018 ISHLT registry analysis) renders the assertion insufficiently substantiated for academic discourse. Furthermore, the recommendation to use pill organizers is laudable but lacks empirical validation in randomized controlled trials. One might posit that digital adherence platforms represent a more rigorous intervention.