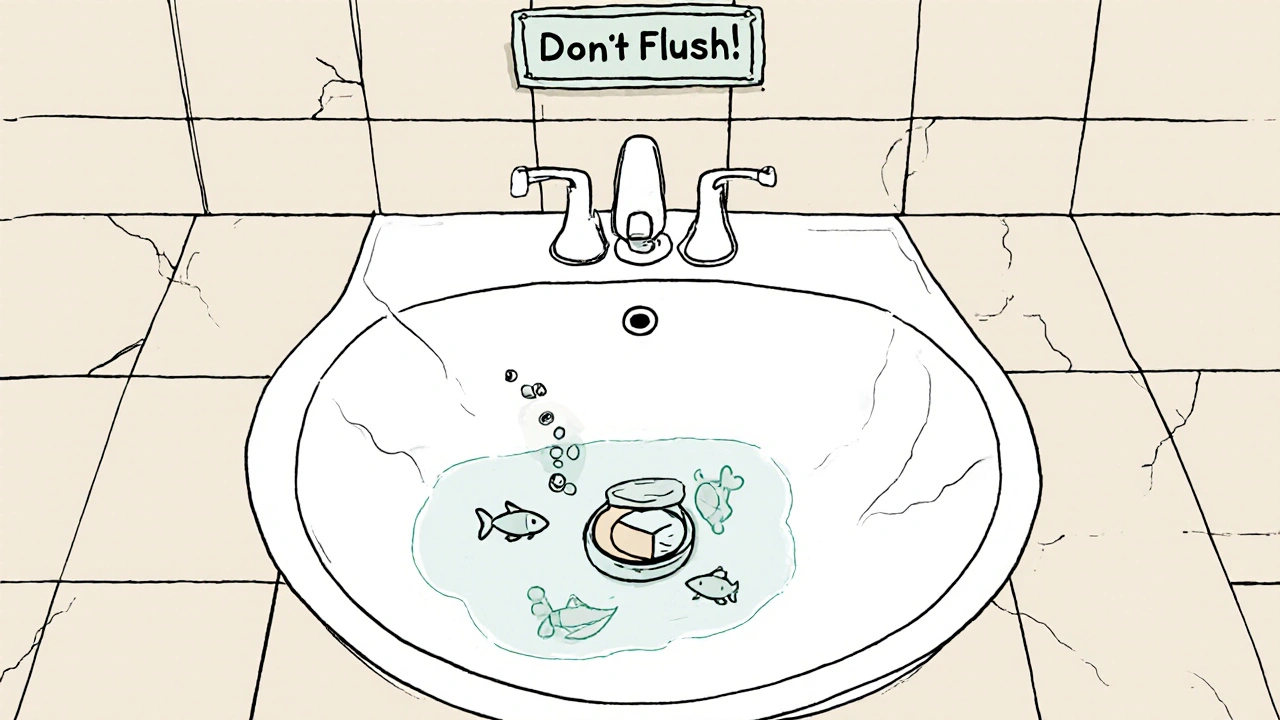

Flushing old pills down the toilet might feel like the easiest way to get rid of them, but it’s one of the worst things you can do for the environment. Every year, millions of unused medications end up in waterways-not because people are careless, but because they don’t know better. The truth is, your bathroom sink isn’t a trash can. And neither is your kitchen trash. What happens when you flush that expired painkiller or leftover antibiotic? It doesn’t disappear. It ends up in rivers, lakes, and even your drinking water.

What Happens When Medications Go Down the Drain

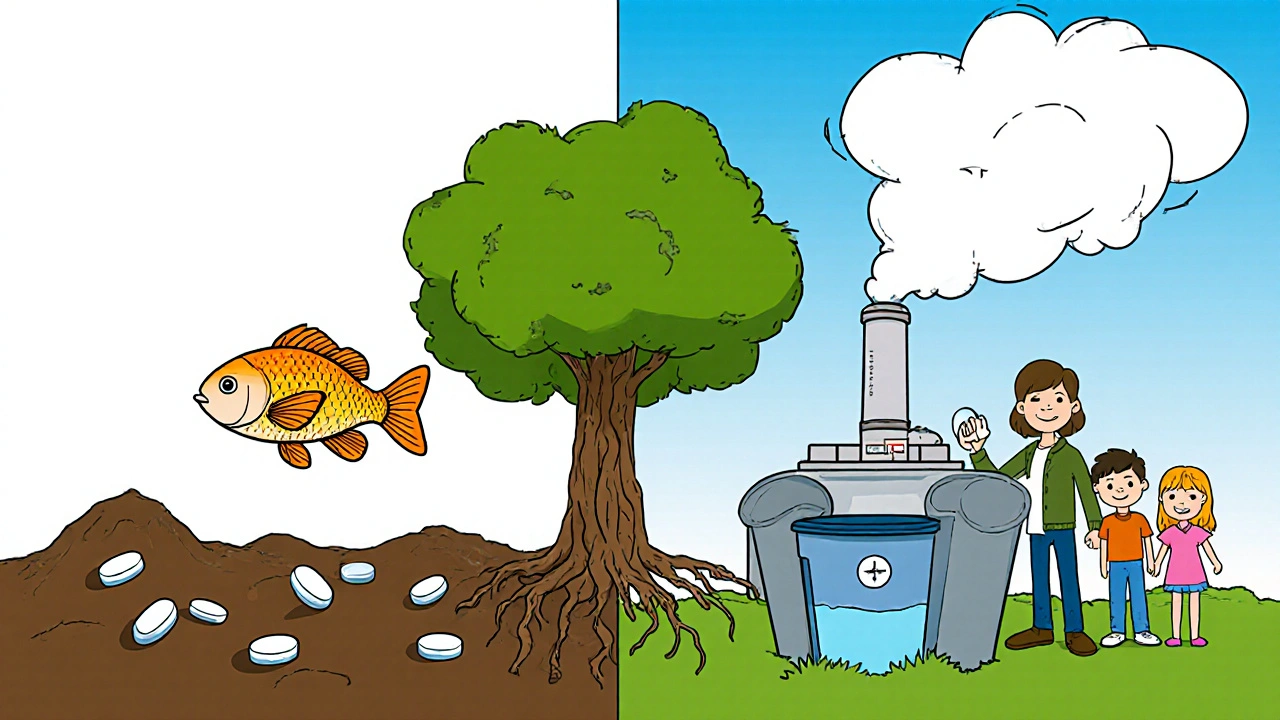

When you swallow a pill, your body doesn’t absorb everything. Only about 20 to 30% of the active ingredient gets used. The rest gets flushed out through urine or feces. That’s one source of pharmaceutical pollution. But when you toss unused pills into the toilet, you’re adding a second, avoidable wave of contamination. These drugs don’t break down easily. Conventional wastewater treatment plants weren’t built to filter out chemicals like ibuprofen, antidepressants, or antibiotics. They’re designed to remove dirt, bacteria, and solids-not tiny, stubborn drug molecules. Studies from the U.S. Geological Survey back in 2002 found traces of over 100 different pharmaceuticals in rivers and streams across 30 states. Since then, the list has grown. Today, scientists detect drugs like acetaminophen, ciprofloxacin, and even cocaine in water samples worldwide. Concentrations are usually low-nanograms per liter-but they’re persistent. And they’re not harmless. Fish in polluted waters have shown signs of hormonal disruption. Male fish developing female traits. Eggs forming inside male organs. These aren’t lab experiments. They’re real animals living in rivers near cities and towns. Why? Because estrogen-like compounds from birth control pills and hormone therapies are entering water systems. These chemicals mimic natural hormones, and aquatic life doesn’t know the difference. Antibiotics in the environment are even more alarming. When fish and bacteria are exposed to low doses of antibiotics over time, it creates the perfect conditions for drug-resistant strains to evolve. This isn’t just an ecological problem-it’s a public health crisis in the making. If bacteria become immune to antibiotics, common infections could become untreatable again.The Myth of the Flush List

You might have heard that some medications are safe to flush. That’s true-but only for a very small number. The FDA maintains a “flush list” of drugs that pose a serious risk if misused, like fentanyl patches or oxycodone tablets. For these, flushing is the safest option to prevent accidental overdose or abuse. But that’s it. Only about 15 medications are on this list. Everything else? Don’t flush it. Many people think if the FDA says it’s okay, then it’s fine. But that’s a misunderstanding. The flush list exists because the risk of someone stealing and overdosing on those drugs outweighs the environmental risk. It’s not an endorsement of flushing. It’s a harm-reduction policy. For the vast majority of your leftover pills-antibiotics, blood pressure meds, cholesterol drugs, sleep aids-flushing is unnecessary and harmful.Where Should You Actually Dispose of Medications?

The best way to get rid of unused medications is through a take-back program. These are collection sites run by pharmacies, hospitals, or local law enforcement agencies. You drop off your old pills, and they’re incinerated under controlled conditions-no leaching, no runoff, no pollution. In the U.S., the DEA runs National Prescription Drug Take Back Days twice a year. But permanent collection sites are still rare. As of 2023, only about 2,140 authorized collection points existed nationwide, and most are in urban areas. Rural communities often have to drive 20, 30, or even 50 miles to find one. That’s a major barrier. In the UK, take-back programs are more widespread. Most pharmacies accept unused medicines. You don’t need a receipt. You don’t need to be the original patient. Just bring the bottle in. They’ll handle it safely. If you’re in Bristol or anywhere else in the UK, check with your local pharmacy. If they don’t have a bin, ask them why. Pressure from customers has led to more programs being added. If there’s no take-back option nearby, the EPA recommends a two-step home disposal method:- Remove pills from their original bottles. Take off or scratch out your name and prescription info.

- Mix them with something unappealing-used coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt. Put the mixture in a sealed plastic bag or container.

- Throw it in the trash.

Why Don’t More People Use Take-Back Programs?

Awareness is the biggest problem. A 2021 FDA survey found only 30% of Americans knew where to return unused medications. Many think expiration dates mean the drugs are dangerous to keep. Others hoard them “just in case.” Some believe flushing is the only option. Reddit threads show how widespread the confusion is. One user, u/EcoWarrior2023, wrote: “I had no idea flushing meds was bad until I read about fish mutations last year-now I drive 20 minutes to the nearest take-back location.” That’s the kind of story that should be common-not rare. Cost and convenience matter too. Home disposal kits like Drug Buster cost around $30 and require mixing chemicals with your pills. They’re effective, but most people won’t spend that much on something they don’t understand. And they’re not available everywhere.What’s Being Done to Fix This?

Europe is ahead of the U.S. on this. The European Union now requires pharmaceutical companies to pay for take-back programs under Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) laws. In 16 EU countries, manufacturers fund collection bins and public education campaigns. It’s working. More people return unused meds, and fewer end up in the environment. In the U.S., California passed SB 212 in 2024, requiring pharmacies to give patients disposal instructions with every prescription. That’s a big step. Other states are watching. The goal is to make safe disposal as normal as recycling. Technologies to remove pharmaceuticals from wastewater are advancing. Ozone treatment and activated carbon filters can remove up to 95% of drug residues. But retrofitting a city’s treatment plant costs between $500,000 and $2 million. That’s not something most municipalities can afford without federal help. The real solution isn’t just better filters. It’s less waste to begin with. Doctors are starting to prescribe smaller quantities. Pharmacies are offering shrink-wrapped blister packs instead of full bottles. Patients are being encouraged to ask: “Do I really need this many pills?”

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to wait for policy changes or new technology. You can act now:- Check your medicine cabinet. Look for expired or unused pills. Don’t wait for a “spring cleaning.” Do it now.

- Find your nearest take-back location. Call your pharmacy. Check your local council website. In the UK, most pharmacies participate. In the U.S., use the DEA’s locator tool.

- Don’t flush. Unless it’s on the FDA’s flush list, don’t flush.

- Ask your doctor. If you’re prescribed a new medication, ask: “Can I get a smaller supply?” or “Is there a non-pharmaceutical alternative?”

- Talk to others. Share what you’ve learned. Your neighbor might not know flushing is harmful. Your parent might still think old pills should go in the trash.

The Bigger Picture

This isn’t just about pills. It’s about how we think about waste. We’ve been taught that throwing things away solves the problem. But nothing really disappears. Everything finds a way back into the ecosystem. Pharmaceutical pollution is a quiet crisis. You won’t see dead fish floating in the river. You won’t smell anything strange in your tap water. But the damage is there-in the genes of fish, in the soil near landfills, in the slow rise of antibiotic resistance. The good news? We already have the tools to fix it. We just need to use them. And that starts with you.Is it ever okay to flush medications?

Yes, but only for a very small list of drugs that pose a high risk of accidental overdose if misused-like fentanyl patches or oxycodone tablets. The FDA maintains this flush list, and it includes only about 15 medications. For everything else-antibiotics, blood pressure pills, antidepressants, pain relievers-flushing is harmful and unnecessary. Always check the FDA’s current list before flushing anything.

Can I throw old pills in the trash without mixing them?

It’s not recommended. Loose pills in the trash can be found by children, pets, or scavengers. Even if they’re expired, some drugs can still be active. The EPA advises mixing them with something unappealing like coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt, then sealing them in a plastic bag before tossing. This reduces the risk of misuse and makes it harder for chemicals to leach into groundwater.

Do take-back programs really make a difference?

Yes. Take-back programs prevent pharmaceuticals from entering waterways and landfills entirely. The drugs are collected and incinerated under strict controls, eliminating environmental risk. Studies show that where take-back programs are accessible and well-publicized, participation rates climb above 60%. In areas without them, improper disposal remains the norm. Accessibility is the biggest barrier-not willingness.

Why don’t all pharmacies offer take-back services?

Cost and regulation. While the U.S. Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act of 2010 allows pharmacies to run collection programs, it doesn’t fund them. Many pharmacies don’t have the budget or space. In the UK, most pharmacies participate because it’s part of national health policy. In the U.S., it’s voluntary. Pressure from consumers has led to growth, but progress is slow. Ask your pharmacist why they don’t offer it-your question might be the push they need.

Are at-home drug degraders worth buying?

They work, but they’re not practical for most people. Products like Drug Buster use chemical powders to neutralize medications, but they cost around $30 per unit and require careful handling. They’re useful if you live far from a take-back site and have a large quantity of drugs. But for most households, mixing pills with coffee grounds and tossing them in the trash is cheaper, easier, and nearly as safe.

What about liquid medications or syringes?

Liquid medications should be poured into a sealable container and mixed with an absorbent material like kitty litter or sawdust before disposal. Never pour them down the drain. Needles and syringes should never go in the regular trash. Use a sharps container (often available for free at pharmacies) and return it to a designated collection site. Many take-back programs accept both pills and sharps.

Can I donate unused medications?

In the UK and most of Europe, donating unused medications is not allowed due to safety and regulatory concerns. In the U.S., a few states have drug donation programs for low-income patients, but they’re rare and have strict rules. Never give away pills-even if they’re unopened. The safest path is always return to a take-back program.

10 Comments

satya pradeep

November 17 2025

Yo, this is wild. I had no idea flushing pills was wrecking fish genomes. I used to just toss old ibuprofen in the trash. Now I mix mine with coffee grounds. Small change, but if everyone did it, we’d cut the pollution in half. Also, why do pharmacies still not have bins everywhere? It’s 2024.

Kathryn Ware

November 19 2025

This is one of those issues that feels invisible until you dig into it. I live in rural Oregon and the nearest take-back site is 45 minutes away. I’ve started hoarding my meds in a locked box until the next DEA event. But honestly? We need more local drop-offs. Pharmacies are literally everywhere. Why aren’t they required to have bins? It’s not like they’re expensive to install. And the FDA flush list? Most people don’t even know it exists. Education needs to be baked into prescriptions, not buried in footnotes. Also, I just started using those little pill bags with the charcoal lining - they’re cheap and work great. No more flushing. No more trash dumping. Just seal, toss, forget.

Jeremy Hernandez

November 20 2025

Of course the government lets Big Pharma off the hook. They don’t want you to know that the real solution is to stop prescribing so damn much in the first place. Why do you need 30 pills for a 5-day infection? They’re making money off waste. And now they’re pushing ‘eco-friendly’ disposal kits for $30? Please. It’s all a scam. The only thing that works is forcing manufacturers to pay for take-back programs - like Europe does. But nope, we’d rather let fish turn into hermaphrodites so shareholders can sleep at night. 🤡

Leslie Douglas-Churchwell

November 22 2025

Okay but have you seen the data on microplastics in pharmaceutical waste? 🤯 The binders in pills? They’re PFAS-laced. So when you flush or trash them, you’re not just releasing drugs - you’re releasing forever chemicals into groundwater. And the EPA’s ‘coffee grounds’ advice? That’s a Band-Aid on a bullet wound. We need federal mandates. We need biodegradable pill casings. We need to ban non-essential prescriptions. This isn’t about ‘responsibility’ - it’s about corporate malfeasance. And don’t even get me started on how the DEA blocks take-back programs in red states. 🚩💧

Prem Hungry

November 23 2025

Let me tell you something - I work in a pharmacy in Delhi, and we’ve been taking back meds for 5 years. No receipt. No questions. Just drop it in the bin. People are surprised at first, but then they start bringing in their grandparents’ old heart pills, diabetes meds, everything. It’s not hard. It’s not expensive. It’s just… common sense. Why can’t the U.S. do this? Is it the fear of liability? Or just laziness? I’ve seen kids in Mumbai pick through trash for pills - and I’ve seen fish in the Ganges with tumors. We don’t need fancy tech. We need systems. Simple ones.

Elia DOnald Maluleke

November 24 2025

One might argue that the human propensity to dispose of pharmaceuticals with the same casualness as a candy wrapper is symptomatic of a deeper ontological dislocation - a rupture between the individual and the ecological totality. We treat the body as a machine to be serviced, and its byproducts as waste to be erased. But the river does not forget. The fish remember. The soil remembers. And the bacteria - oh, the bacteria - they evolve in silence, whispering the future in the language of resistance. To flush is to deny kinship. To discard is to sever the thread. Perhaps the real question is not how to dispose of pills, but how to reweave ourselves into the web of life.

shubham seth

November 25 2025

Let’s be real - flushing meds is the dumbest thing humans do besides leaving the fridge open. But here’s the kicker: the people who do it? They’re not evil. They’re just clueless. And the system? It’s designed to keep them clueless. Pharmacies don’t advertise take-back bins because they don’t want you to think about what happens after you buy the pills. Doctors don’t ask ‘Do you need all 30?’ because they get paid per script. The FDA’s flush list? A distraction. A magic trick. ‘Look over here while we let 99% of your toxic trash go into the water.’ Wake up. This isn’t environmentalism. It’s survival.

kora ortiz

November 25 2025

Just did my medicine cabinet cleanup today. Found 3 expired antibiotics, 2 anxiety pills, and a bottle of old thyroid med. Took them to the CVS down the street - they had a bin right by the pharmacy counter. No hassle. No judgment. Just dropped them in. If you haven’t done this yet - do it today. Your local river will thank you. 🌱💧

Bill Machi

November 27 2025

Who cares if a few fish turn weird? We’ve got bigger problems. Climate change, inflation, border security - this is just green virtue signaling wrapped in a lab coat. The water’s still drinkable. The fish still swim. The economy still turns. Stop pretending your little pill disposal ritual fixes anything. Real patriots focus on real threats.

Eric Healy

November 29 2025

My dad used to flush his blood pressure meds. He died last year. I found his stash in the bathroom cabinet. All still good. I wish he’d known. I wish we’d talked about it. Now I make sure everyone in my family knows: don’t flush. Don’t toss. Don’t hoard. Take it back. Simple. If you can buy it, you can return it. That’s not radical. That’s just basic.