Oral Mucositis: What It Is and How to Manage It

If you’ve heard the term oral mucositis, you probably know it can make meals miserable. When dealing with oral mucositis, painful inflammation of the mouth lining that often appears during cancer therapy. Also known as mouth sores, it turns eating, speaking, and even brushing your teeth into a challenge.

It is most commonly triggered by Chemotherapy, drug regimens that attack fast‑growing cells, including those in the mouth or Radiation therapy, targeted beams that can inflame oral tissue when aimed at the head and neck. Both treatments disrupt the natural turnover of mucosal cells, leaving the lining raw and vulnerable. That’s why you’ll often see oral mucositis listed alongside other chemotherapy side effects like nausea or hair loss. The condition isn’t just about pain; it can lead to infection, weight loss, and treatment delays.

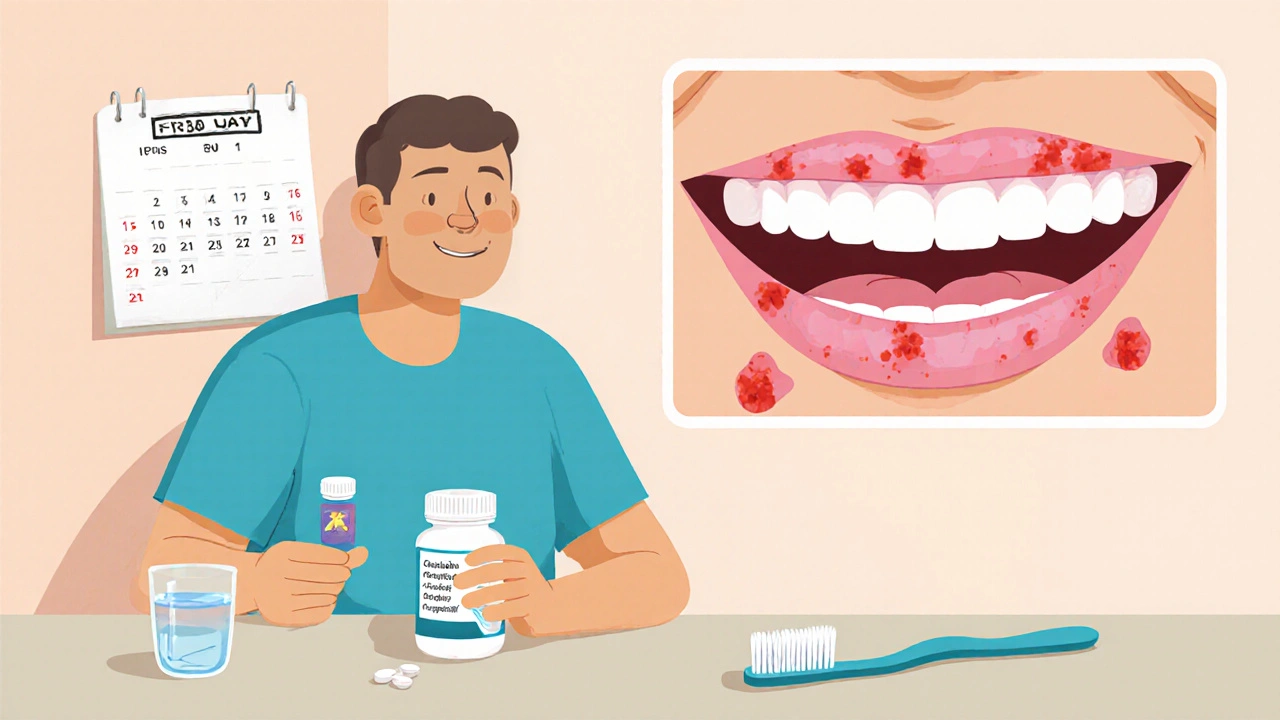

One of the biggest risks after the lining breaks down is a secondary infection, especially from Candida yeast. Here Fluconazole, an oral antifungal medication often steps in. It’s prescribed when patients develop thrush or other fungal overgrowths that thrive in the moist, damaged environment. Using fluconazole early can keep the infection from turning a sore into a full‑blown ulcer, which in turn helps maintain nutrition and reduces the chance of needing a treatment pause.

Key Strategies to Reduce Oral Mucositis

Good oral hygiene is the first line of defense. Gentle brushing with a soft‑bristled toothbrush, a fluoride‑free toothpaste, and regular rinses with saline or mild chlorhexidine keep bacterial load low without irritating the tissue. Many clinics also recommend a bland diet—think mashed potatoes, smoothies, and oatmeal—to avoid abrasive foods that can scrape the lining. Hydration matters, too; sipping water or non‑acidic drinks every few minutes keeps the mouth moist and helps flush out irritants.

Beyond basic care, clinicians often suggest topical agents like benzydamine mouthwash or low‑dosage oral lidocaine to numb the pain. For those who can tolerate it, a short course of systemic analgesics such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen can ease discomfort. Nutritional supplements rich in glutamine have shown promise in some studies, as the amino acid supports mucosal healing. If you’re already on medications like Lisinopril that cause a dry cough, discuss alternatives with your doctor—dry mouth can worsen mucositis.

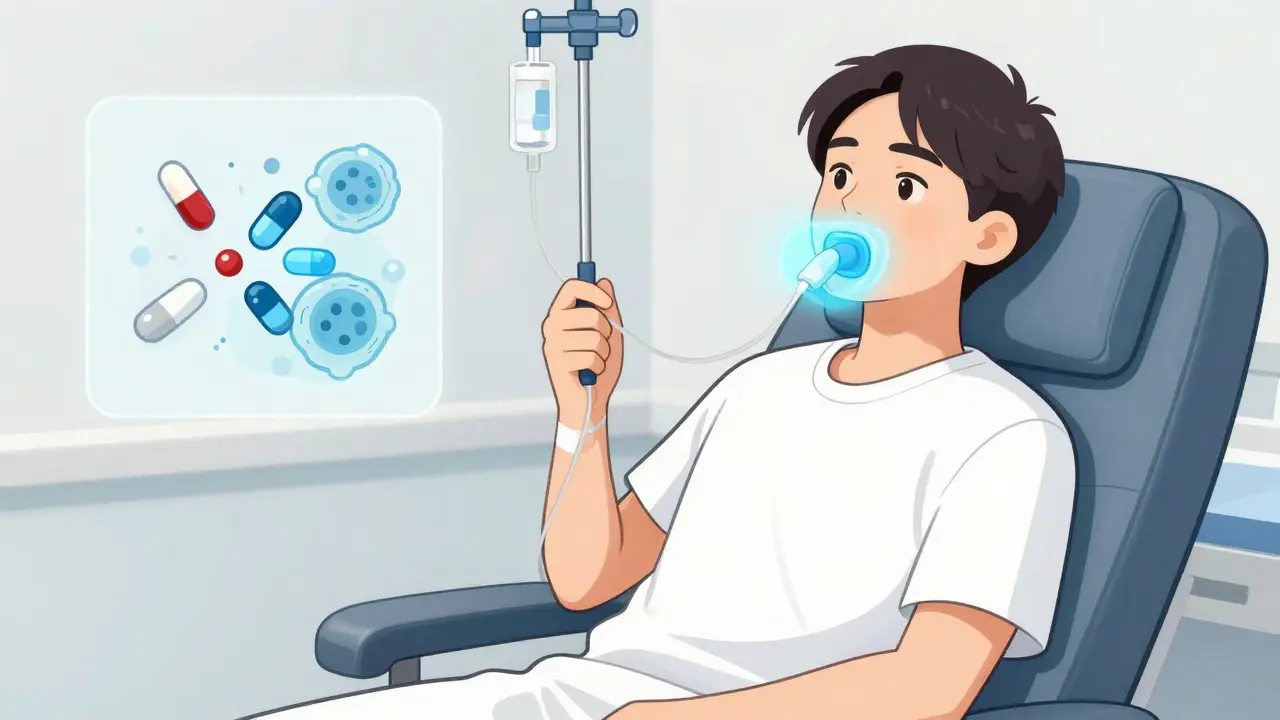

When prevention isn’t enough, advanced options come into play. Low‑level laser therapy (LLLT) has gained traction for its ability to accelerate tissue repair and reduce pain. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is another niche approach, delivering extra oxygen to damaged cells to speed healing. Both require specialist equipment, but many cancer centers now offer them as part of an oral care protocol.

Managing oral mucositis is a team effort. Your oncologist, dentist, nutritionist, and pharmacist each bring a piece of the puzzle—whether it’s adjusting your chemo schedule, recommending a mouthwash, or prescribing fluconazole if a fungal infection appears. By staying proactive with hygiene, diet, and symptom monitoring, you can keep the sores from derailing your treatment.

Below you’ll find a hand‑picked collection of articles that walk through prevention tips, treatment options, and real‑world experiences, giving you a clear path to handle oral mucositis while staying on track with your cancer care.